Since Meditation 1, members have been actively discussing meditation, and writing about their own practice preferences and experiences. Interest was raised by podcast 9 in which John Bolwell talked about martial arts, their relevance to middle way philosophy, and as a meditative practice. In this blog I offer a digest of the interesting and sometimes contentious issues raised by John’s podcast (and the comments that ensued), and I shall go on to describe the basics of my own current practice, why I’ve adopted it, how I experience it, and what I believe it offers as an alternative to sitting meditation, or as a complementary adjunct.

Meditation is quite likely to conjure up an image of someone sitting (or squatting) on the ground, cross-legged, with hands loosely placed in the lap, or rested palms downward on the thighs. The eyes are closed or half-closed, the head is erect, the back straight. The facial expression is enigmatic, or might be described as calm or ‘serene’, with a half-smile on the lips

Images like this are nowadays quite commonplace, and I feel justified in claiming that most people would associate meditation with sitting in the posture described. I am slightly troubled by this. It’s as if the image has become a ‘brand’; indeed, the image of someone ‘meditating’ has been used widely to sell commodities ranging from air-fresheners to disposable nappies. It’s not the commodification of meditation that concerns me, it’s the imperative that – for me – the image seems to imply: This is the way you meditate. You sit. On your bottom. On the floor. There is no reliable alternative. This method enjoys authoritative sanction. From the very top.

Rightly or wrongly, I associate this dogmatism with mainstream Buddhism. I think I may not be alone in this respect, at least in its application to practice. It ought not, I think, cross over to migglism, where the development of new forms of practice seems to be part of our agenda.

About three years ago I came across the practice called “standing like a tree”. It’s a form of qi gong. It’s widely practised and written about, but it’s not a practice that has been much associated with Buddhism here in the West. As John Bolwell claims, qi gong is as much a meditative practice as it’s a kind of strengthening or health-giving exercise. With just over two years of pretty consistent practice using the method, I think that its meditative possibilities match those of sitting, and in some respects I think they’re broader and deeper.

How to do it? Stand with feet slightly apart, knees unlocked. Let arms fall to their sides. Enjoy the feeling of standing. Allow the body to move, supported by the softening feet and ankles, and imagine your feet taking root in the earth (floor, pavement etc.), so that your weight, and any tension or heaviness you experience, drains down into the earth. From the knees up, feel energy rising up to the sky. Allow your body to relax and to soften, but also to move, to breathe, and to feel.

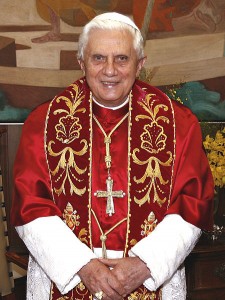

Let the body balance itself, aligning itself with the earth through its centre of gravity. You can’t do this by thinking about it, any more than you can think a key into fitting itself into a lock. By letting the body move subtly, in a thousand different tiny adjustments, it finds its own alignment with the earth, and becomes (as it were) weightless, and effortlessly self-supporting through the spine (see image immediately below). This requires patience, and letting go. Alignment is recognised by an unmistakable sense of “fit”, like the feeling of a key fitting into a lock it’s designed to open.

Aligned, relaxed, effortless poise*

Aligned, relaxed, effortless poise*

Then, gradually explore breathing, moving and attending, bringing these components of experience together. How? It depends on you, your body, and your patterns of holding yourself. Just keep mixing your breathing, moving and attending – in relaxed and exploratory ways – until it takes very little or no effort to stand; no more than it takes to sit. Patterns of holding gradually (over many sessions) give way to new freedoms, of thinking, feeling and responding. And new insights emerge as energies ‘trapped’ in habitual holding patterns are released, and integrated.

The ‘full’ exercise combines this process of relaxation, attending and moving with careful re-positioning of the arms, in new postures, which give rise to subtle experiences of the re-direction of energy throughout the body. As Robert points out elsewhere, the experience of ‘energy’ is subjective; one cannot categorically or dogmatically say that this is the experience of ‘energy’, but the word conveys the subjective experience for some.

More detailed instructions are available from George Draffan’s website at www.NaturalAwareness.com, and I acknowledge my adapting some of the material above, and my own development through using it, to George, with deep gratitude.

It’s suggested that it takes about 100 sessions to get used enough to the practice for it to communicate its value, and it’s recommended that you start with short sessions, no more than five minutes, building capacity and commitment gradually, in small increments: “little and often” is the watchword. The practice can be combined (if you wish) with sitting meditation or, if you choose to do so, it may supplant sitting as your principal practice, leaving you the option of sitting as an adjunct if you wish it. I have no aversion to sitting, although I grouse about its being, or seeming to be, the default practice for meditators.

‘Standing like a tree’ doesn’t require, nor does it recommend, closing one’s eyes. I meditate usually with eyes open and unfocussed (or relaxed). I don’t find that this interferes with attention, nor does it necessarily distract me. It’s my experience that balanced attention to experience is best achieved when all sensory modalities are accessible. This is perhaps a matter for individuals to discern for themselves; and I don’t think closed eyes should be seen as the default position, as it seems to be generally and unquestioningly accepted.

‘Standing like a tree’ lends itself, unlike sitting, to practice in everyday situations. Most of our waking time is spent erect, in some kind of motion, and in situations that require the kind of otherwise unaware alignment with the earth that makes purposive and useful action possible. In this important sense the practice may be more congruent with everyday life and human behaviour. Sitting meditators often lament the apparent ‘gulf’ they experience between ‘time on the cushion’ and life in general. Standing like a tree may bridge that experiential gap.

I recognise that the method I’ve described briefly above may seem alien to some, and unachievable by others (including people who have difficulty standing, or those who are physically incapable of doing so unaided). I offer it tentatively, and respectfully for consideration. I’m open to further questions and observations. I admit to no special level of expertise in the matter, either from a practical or from a theoretical point of view. All the opinions expressed are my own, based on and within the limits of my personal experience and understanding.

* picture copied from Google images

The following pictures (taken by my wife) are of me, in each of the five positions making up the ‘full standing-like-a-tree set’, and in the suggested sequence. Not all are in any sense strictly necessary, and each may be maintained for as long as one wishes to, and is able to comfortably. Reading from right to left, starting at the top, are shown: the start position, arms to their sides (this position is returned to briefly between all changes of position, and at the end); “big belly” position; “balloon at chest” position; “pushing balloon at face” position; “standing in the stream” position. In my own daily practice I maintain each of these positions for between 5 and 10 minutes, usually (not always) without any tiredness.