[WpProQuiz 1]

Monthly Archives: December 2014

The MWS Podcast 42: Lancaster Co-housing project resident Mary Searle-Chatterjee

My guest today is Mary Searle-Chatterjee, a retired anthropologist and resident of the Lancaster Co-housing Project which won the Observer Ethical Award for 2014. She’s going to tell us something about the history, aims and values of the project and she’s also kindly agreed to give us a tour of the place. I went along with my camera too so the slideshow is maybe worth a look.

MWS Podcast 42: Mary Searle-Chatterjee as audio only:

Download audio: MWS_Podcast_42_Mary_Searle_Chatterjee

The Trouble with Economics

If you were to ask which group of academics had the most direct influence over the state and destiny of our society, a good bet would be those of economics. They mould the thinking of the economics graduates of tomorrow, who go on to advise, possibly even run, banks, businesses, governments and international institutions. Yet this same group of academics is by all accounts the most dogmatic of them all, with academic power and influence across the globe staying exclusively with one group of thought (the neo-classical), who monopolise the most prestigious economics journals, the appointments for academic posts, and the shape of economics syllabuses in universities. The ideas of these people have massive power over the world, and yet the inadequacy of their ideas becomes immediately obvious to anyone who looks out beyond the narrow assumptions of their mathematical models. This is a disastrous example of the power of the self-justifying left hemisphere in action.

I have become increasingly aware of this recently when writing about economics as (a small) part of my new book, when I discovered that there is a growing protest movement amongst economics students protesting against the narrowness of the teaching they receive. My perception of the disastrous impact of academic economics has been reinforced by listening to an excellent radio programme from BBC Radio 4, in which Aditya Chakrabortty provides widespread evidence both of the narrowness and its consequences. I highly recommend this programme, which is linked here (on BBC iplayer, which means it will only be available for 30 days and only within the UK). It’s 38 minutes long but well worth that expenditure of time. The people interviewed by Chakrabortty admitting the huge inadequacies of academic economics include a big cheese from the Bank of England, billionaire George Soros (who said he made his fortune by ignoring his economics training) and some eminent (but still marginalised) economists such as Robert Skidelsky and Ha-Joon Chang, as well as a great many frustrated students from around the globe.

The situation in economics sounds very similar to the one I encountered as a postgraduate student in philosophy: the ascendency of a narrow view of the subject is maintained by a positive feedback loop. Only the people with the mainstream assumptions get published in the most prestigious journals. Only the people who publish in those journals stand any chance in the massive competition for academic jobs. Once they get there, those people have sunk costs and vested interests that make them very slow to change anything, and their ability to support the beliefs of the powerful ensures that they are never seriously challenged. They just mould the next generation and the cycle continues.

In evolutionary terms, this would involve selection for narrow-mindedness and fragility, where people who flourish in certain very restricted conditions but take no account of wider uncertainties continue to rule – until they bring the whole of their society down with them. The only difference between philosophy and economics in this respect is that the effects of philosophy on society are much slower and more long-term than those of economics, whereas people can see the defects of narrow economic thinking clearly and amply demonstrated in the crash of 2008.

In the chapter on economics in my forthcoming book, I identify five common and influential dogmas in economics – all dogmas that can be related to wider ones beyond economics. These are:

- Rational choice theory, which assumes that a unified self will make consistent consumption choices

- Perfect information, which assumes that people know what is happening in the markets they are participating in

- Cosmic justice in a free market: i.e. Adam Smith’s ‘Invisible Hand’, which ensures that the narrow choices of individuals will be transformed by the power of the market into general good by helping to create wealth

- The growth model, which assumes infinite resources can be used for unending growth (or that growth can somehow be decoupled from a lack of new resources)

- Profit maximisation, which assumes that the best strategy for a company is always to maximise profit, whilst other motives (e.g. those of fair trade) simply distort the functioning of the market

It is not as though these assumptions have no challenges in the wider world. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel Prize for demolishing rational choice theory. The Invisible Hand has long been questioned by left-wingers, whilst the growth model has long been questioned by Greens, and is cogently deconstructed by green economist Tim Jackson. The movement for corporate social and environmental responsibility, including the fairtrade movement, also offers a challenge to profit maximisation. Above all, Nassim Nicholas Taleb provides a strong challenge to the over-certainties of economics (see my review of his book Antifragile). There are also plenty of alternative models being developed (such as Tim Jackson’s account of prosperity without growth), so the criticism is not merely destructive. But all this criticism from the voices of experience seems to make little or no impression on the self-sufficient, self-reinforcing dogmatic bubble of the core academic discipline.

Of the five dogmas above, the one that concerns me most is the fourth. The growth model appears to be analogous to a car that is constantly accelerating because it is being chased by a police car of debt, speeding along behind it. But it is only a matter of time before the car crashes, runs out of petrol, or runs out of road, at which point the debt police car will also catch up with it. In this respect it just provides a particularly urgent and striking model of the dangers of metaphysical dogma. All dogmas, in some ways, speed up to try to preserve themselves, pursued by police cars of wider conditions, and then they crash. But it seems, at present, as though the economists will do for us long before the other dogmatists get close to doing so.

Paul Signac 1863 – 1935 and Joseph Albers 1888 – 1976. Two Colour Theories

Colour is used by painters in many ways, cave painters would grind the earth around them to mix with water to create reds, ochres and browns to draw animals, Italian Renaissance painters would often depict the Virgin Mary clothed in blue, blue paint was derived from very expensive lapus lazuli to symbolise the esteem in which she is held in the Catholic Church, another symbolic colour is gold that was used by Byzantine artists. As time went by many new colour theories arose, here are two .

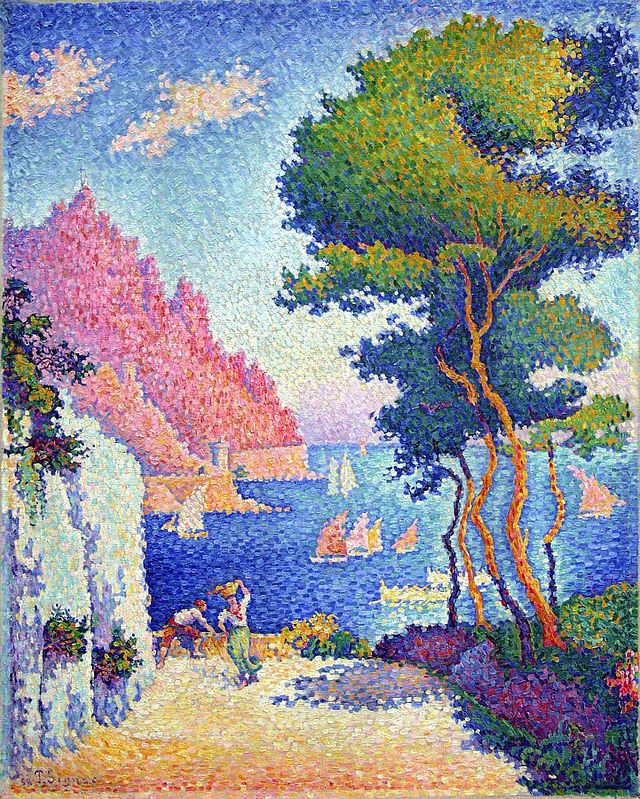

Pointillism. Capo di Noli Italy. 1898.

Paul Signac was born on Paris and began his career studying architecture but then changed his mind and took up painting when he was eighteen after seeing the work of Matisse, he studied the colour theory explained and used by Georges Seurat, they were two French painters who belonged to the group called Neo-Impressionists , Seurat developed the use of pure colour which he applied to his canvases in the form of dots which became known as the Pointillist style having abandoned the Impressionist method of painting with short brushstrokes, it was slow patient work, this experiment meant using scientifically juxtaposed small dots of pure colour which were intended to blend not on the canvas but on the eyes of the viewers. Signac learnt a great deal about this technique from Seurat, they became friends. Signac liked to sail around the coasts of Europe painting landscapes and making water colour paintings of French harbour scenes, the sunlight on the south coast produced sparkling seas and heightened colour. He had met Seurat and also Monet in 1884, Van Gough and Gaugin were also painting at this time. Signac was very interested in the ideas of anarchist communism but had to tone down these ideas in order to gain public acceptance.

I have chosen the painting called Capo di Noli 1898. The sparkling colours expressing the sunshine of Italy are seen in this sea – side view, whether or not you think the colours have merged to create a flat plane is left for the viewer to decide, the brush strokes of the Impressionists rather than dots of colour are perhaps more easily accepted? The shadows are in pale to dark violets set alongside the yellows of the sandy ground. Matisse experimented with pointillist painting but just for a short time.

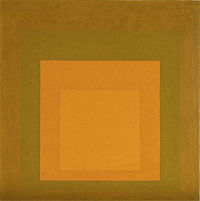

Homage to the Square 1965.Joseph Albers.

Homage to the Square 1965.Joseph Albers.

Joseph Albers was a German-born American artist who after studying with Johannes Itten at the Bauhaus school was asked by its founder and director Walter Gropius to join the stained glass department to teach foundation students, he also worked with Paul Klee designing glass and furniture. In 1925 the school moved to Dessau, there Albers met a student, Anni, whom he married, he worked there until in 1933 the Nazis closed the school and the artists dispersed. Albers went to live and work as a professor of art at the art school Black Mountain College in North Carolina. In 1950 he left to head the department of design at Yale University, he retired in 1958.

In 1963 he published ‘interaction in Colour’ to demonstrate his theory ‘that colours are governed by an internal and deceptive logic.’ He favoured a very disciplined approach to composition and painted hundreds of works in ‘ Homage to the Square’ in which he explored the chromatic interactions with nested squares. I remember when we students would experiment in a similar way with colour, for example we painted the same colour with a different coloured background, this showed clearly how the colour seemed to change, becoming darker or lighter, or more bright, our colour perception was changed. Albers paintings consisted of three or four squares of solid planes of colour nested within one another. These studies made very interesting viewing I think, although we see a flat surface which seemed to contain no symbols or metaphor in a left brain hemisphere way they do possess a beauty and balance that enriches our sense of colours working together. I wonder what you make of this painting. Mark Rothko painted large canvases with what looks at first like simple flat colour, but there is activity at the edges of the squares and oblong shapes he uses, the intensity and depth of colour can envelop the viewer – perhaps.

images from wikipedia.