Spoiler Alert: This isn’t a synopsis or a review but I will reveal certain, important, plot points. As such, if you haven’t yet seen it yet – and would like to – you may want to stop reading now.

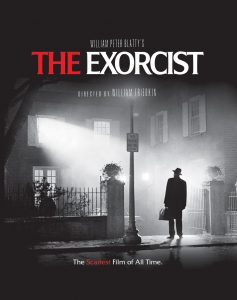

Cursed. Obscene. Scary. Nauseating. Pea Soup. These are just a selection of words  associated with William Friedkin’s 1973 film, The Exorcist (adapted from William Peter Blatty’s novel of the same name). The Exorcist tells the story of the Exorcism of 12-year-old girl, Regan MacNeil, who has been possessed by a malevolent force. It is set in affluent 1970’s Georgetown USA, where Regan lives with her atheist mother, who also happens to be a famous actress.

associated with William Friedkin’s 1973 film, The Exorcist (adapted from William Peter Blatty’s novel of the same name). The Exorcist tells the story of the Exorcism of 12-year-old girl, Regan MacNeil, who has been possessed by a malevolent force. It is set in affluent 1970’s Georgetown USA, where Regan lives with her atheist mother, who also happens to be a famous actress.

Even in the early 1990’s, when I was at school, this film had a reputation as being the most disgusting and frightening film ever made – which of course meant everybody wanted to see it. This desire was only intensified by the fact that The Exorcist had been banned in the UK since 1984; a few friends and I even attempted to watch a pirated copy of it on VHS, but  our excited anticipation was soon extinguished once we realised that the video quality was so bad as to render further viewing impossible. In 1998 the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) lifted the ban, and The Exorcist was released – with much fanfare – in cinemas across the country. Many of my peers came back with reports of disappointment and boredom. ‘It’s not scary at all. I didn’t jump once’ they’d say, or ‘I don’t know what the fuss is about, nothing even happens for most of the film’. I was worried. I’d recently read the book and really enjoyed it, but wasn’t sure how it would be translated into the ‘Scariest Film Ever Made’. Could this really be the same film that had caused people to faint and vomit while watching it? I knew loads of people who’d seen it the first-time round and refused to even talk about it, let alone watch it again. Perhaps it hadn’t aged well?

our excited anticipation was soon extinguished once we realised that the video quality was so bad as to render further viewing impossible. In 1998 the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) lifted the ban, and The Exorcist was released – with much fanfare – in cinemas across the country. Many of my peers came back with reports of disappointment and boredom. ‘It’s not scary at all. I didn’t jump once’ they’d say, or ‘I don’t know what the fuss is about, nothing even happens for most of the film’. I was worried. I’d recently read the book and really enjoyed it, but wasn’t sure how it would be translated into the ‘Scariest Film Ever Made’. Could this really be the same film that had caused people to faint and vomit while watching it? I knew loads of people who’d seen it the first-time round and refused to even talk about it, let alone watch it again. Perhaps it hadn’t aged well?

When I did eventually get to see it that I could understand why my peers were confused about the reputation it had achieved. I’m not the kind of person that finds Horror films particularly scary anyway, but I had expected The Exorcist to be an exception. It wasn’t. In this respect, the length of time that had passed since its original release did seem to have had an impact. Horror films throughout the 90’s had a tendency to reject the kind of subtle psychological techniques used in the 60’s and 70’s in favour of ‘jump scares’ and ‘gore effects’. Therefore, that is what any teenager going to see a Horror movie at this time would be expecting. That’s not what they got with The Exorcist. There’s hardly any ‘gore’ and it is almost entirely void of ‘jump scares’. In addition to this, much of imagery was much less shocking in the 90’s than I suspect it would have been to a 70’s audience. With these considerations in mind I can understand many of my peer’s sense of disappointment – in this respect it had not lived up to the hype. However, as much I wasn’t scared in the cinema, I loved it. I found it absorbing in a way that few films had been and was surprised by the skilful way in which it created an atmosphere. The deep layers of meaning hidden within the imagery and narrative demanded repeated viewing. It is a deeply unsettling film and I found that it stayed with me (as the book had) long after I’d left the cinema; something that did not happen with contemporary horror films such as ‘I Know What You Did Last Summer’ (which is instantly forgettable). While it wasn’t what the hype had lead me to believe it would be, The Exorcist, as a film, had aged very well indeed.

After a period of about 10 years, where I watched it quite a lot, I spent a further 10 years without seeing it at all. That is, until a few months ago, when I heard Mark Kermode (film critic and Exorcist expert/ super-fanboy) discussing it on the radio. With some trepidation  – I feared that it really might have aged badly by now – I sought out a copy and sat down to watch it again. I needn’t have worried, it stands up incredibly well & I enjoyed it just as much (if not more) than I had before. More importantly for this blog however, I also realised that it related, both stylistically and narratively, to the Middle Way.

– I feared that it really might have aged badly by now – I sought out a copy and sat down to watch it again. I needn’t have worried, it stands up incredibly well & I enjoyed it just as much (if not more) than I had before. More importantly for this blog however, I also realised that it related, both stylistically and narratively, to the Middle Way.

Watching The Exorcist is a physical experience. I know that watching any film can be described as a physical experience, we are embodied beings after all, but The Exorcist goes further. You can feel the cold of Regan’s bedroom. You can smell her necrotic breath as she lies, unconscious on the bed. I don’t understand what cinematic tricks are used to create this effect but I suspect that it has as much to do with the sound as it has with visuals. The ambient sound is hypnotic and the groaning rasp that accompanies Regan’s breathing creates a powerful and absorbing effect. There are other scenes where the combination of visuals and sound work together to create the experience of embodied physicality, such as when Regan is made to undergo a range of intimidating and painful medical tests.

On the surface, The Exorcist is a fairly standard tale of good versus evil; light overcoming darkness. During the first scene – where an elderly Jesuit priest, Father Merrin, is seen attending the archaeological excavation of an ancient Assyrian site in northern Iraq – the contrast between quiet contemplation and loud commotion is jarring. While the scene is set within the suffocating glare of the desert sun, it is also pierced with dark imagery. It’s within this context that we finally see an increasingly disturbed Merrin wearily, but defiantly, facing a statue of the Assyrian demon Pazuzu. It is no coincidence that this scene brings vividly to mind the Temptation on the Mount, where Jesus overcame Satan’s attempts to divert him from his holy path to righteousness. I’m sure that this premonition of the battle to come, is constructed and representative of several Jungian archetypes, but I’m not familiar enough to identify them all. However, I’m confident that there’s the Hero, the Shadow, God and the Devil; the latter two also being representations of two metaphysical extremes: absolute good and absolute evil. The key point however is that Father Merrin is not God (or even Jesus) and the statue is not the Devil (or even Pazuzu), they are both the imperfect embodiments each.

On the surface, The Exorcist is a fairly standard tale of good versus evil; light overcoming darkness. During the first scene – where an elderly Jesuit priest, Father Merrin, is seen attending the archaeological excavation of an ancient Assyrian site in northern Iraq – the contrast between quiet contemplation and loud commotion is jarring. While the scene is set within the suffocating glare of the desert sun, it is also pierced with dark imagery. It’s within this context that we finally see an increasingly disturbed Merrin wearily, but defiantly, facing a statue of the Assyrian demon Pazuzu. It is no coincidence that this scene brings vividly to mind the Temptation on the Mount, where Jesus overcame Satan’s attempts to divert him from his holy path to righteousness. I’m sure that this premonition of the battle to come, is constructed and representative of several Jungian archetypes, but I’m not familiar enough to identify them all. However, I’m confident that there’s the Hero, the Shadow, God and the Devil; the latter two also being representations of two metaphysical extremes: absolute good and absolute evil. The key point however is that Father Merrin is not God (or even Jesus) and the statue is not the Devil (or even Pazuzu), they are both the imperfect embodiments each.

Understandably perturbed by her daughters increasingly disturbing behaviour, Regan’s mother seeks the help of neurologists and then physiatrists. Both fail to identify a cause and both fail to succeed in their interventions. Eventually, the perplexed psychiatrists suggest that Regan’s exasperated mother enlist the services of a priest, to which she reluctantly agrees.

The priest that she finds is a man called Father Damian Karras. Karras is unlike Merrin, whose background is not really explored, in that he is clearly a conflicted and complex character. We see him caring for his elderly mother, when no one else seems willing to, and we also see him, dressed in his Jesuit regalia, turn away from a homeless man who asks for his help. Karras, then, is not a bad person, but neither is he that good. The viewer is left to wonder the nature of this priest’s faith. When we add to this the fact that he is a scientist (psychiatrist) as well as a priest, we start to see the depiction of a complex, multifaceted individual who struggles, in all aspects of his life, through the messy middle in which we all exist.

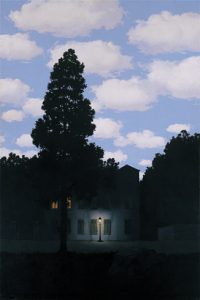

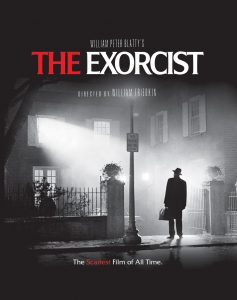

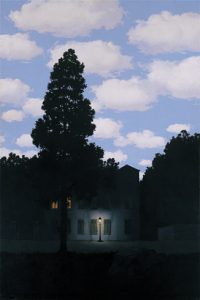

Karras, who is not qualified to perform the Exorcism ritual, convinces the Church of Regan’s need and Father Merrin is subsequently called upon. The moment when he arrives at the house and looks up at the room which contains the possessed girl is inspired by The Empire of Light, a series of pictures painted by René Magritte in 1953-4. As with the opening sequence, we are shown our archetypes juxtaposed in preparation for battle; this striking image was also used as the now famous promotional poster (which I used to have on my bedroom wall). The clichéd battle between good and evil begins. Except it doesn’t… not really. Like the statue of Pazuzu, Regan is not an absolute representation of evil; she has been embodied by evil but is not the embodiment of it – she’s a 12-year-old girl. Father Merrin is not the embodiment of good, he is just a representative of Christ (and therefore God). This is made explicitly clear (if it wasn’t already) in an extended scene where the two priests desperately shout, ‘the power of Christ compels you, the power of Christ compels you’ over and over while throwing Holy water on the levitating girl. A lesser film would have Merrin eventually defeat the demon and save the girl, but this is not what happens. The elderly Exorcist dies during the gruelling exchange and Karras is left facing the demon alone. Again, a lesser film would have Karras take up the role of Exorcist and overcome the evil force against all odds. This is not what happens. Religion, like science before it has failed and Karras appears to be in a hopeless predicament. In the heat of the moment he takes the only course of action that he feels is available to him; he grabs Regan and shouts

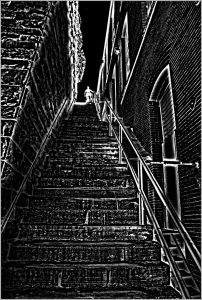

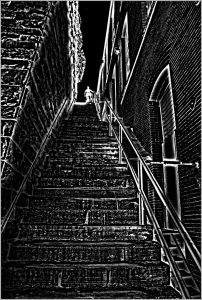

Karras, who is not qualified to perform the Exorcism ritual, convinces the Church of Regan’s need and Father Merrin is subsequently called upon. The moment when he arrives at the house and looks up at the room which contains the possessed girl is inspired by The Empire of Light, a series of pictures painted by René Magritte in 1953-4. As with the opening sequence, we are shown our archetypes juxtaposed in preparation for battle; this striking image was also used as the now famous promotional poster (which I used to have on my bedroom wall). The clichéd battle between good and evil begins. Except it doesn’t… not really. Like the statue of Pazuzu, Regan is not an absolute representation of evil; she has been embodied by evil but is not the embodiment of it – she’s a 12-year-old girl. Father Merrin is not the embodiment of good, he is just a representative of Christ (and therefore God). This is made explicitly clear (if it wasn’t already) in an extended scene where the two priests desperately shout, ‘the power of Christ compels you, the power of Christ compels you’ over and over while throwing Holy water on the levitating girl. A lesser film would have Merrin eventually defeat the demon and save the girl, but this is not what happens. The elderly Exorcist dies during the gruelling exchange and Karras is left facing the demon alone. Again, a lesser film would have Karras take up the role of Exorcist and overcome the evil force against all odds. This is not what happens. Religion, like science before it has failed and Karras appears to be in a hopeless predicament. In the heat of the moment he takes the only course of action that he feels is available to him; he grabs Regan and shouts  at the demon, ‘take me, take me’. The demon gladly obliges and, a now possessed, Karras – who already exists somewhere between good and evil – is able to throw himself out of Regan’s window, where upon hitting the ground he falls down a flight of steep stairs, where he dies, presumably taking the demon with him and leaving Regan to make a full recovery.

at the demon, ‘take me, take me’. The demon gladly obliges and, a now possessed, Karras – who already exists somewhere between good and evil – is able to throw himself out of Regan’s window, where upon hitting the ground he falls down a flight of steep stairs, where he dies, presumably taking the demon with him and leaving Regan to make a full recovery.

Science, religion and the explicitly archetypal forces of good have not triumphed over evil and, in this muddled mess, appeals to authority do not always provide the promised solutions. Instead our Middle Way hero, who’s able to hold onto his beliefs lightly, is left to address challenging conditions as they arise. The solution he finds, I would like to suggest, seems remarkably like an extreme example of the ‘two donkeys’ analogy that is a favourite of this society. By integrating competing desires, he is able to overcome conflict, albeit at great cost to himself.

running for 13 months from Dec 2018 to Dec 2019. There will be a variety of topics, all of which involve the relationship between an area of practice or interest and the Middle Way – for example, the Middle Way and Meditation, the Middle Way and Science, the Middle Way and Judaism. This is your opportunity to find out more about a Middle Way perspective in relation to a topic that already interests you, interacting with members of the society in real time online.

running for 13 months from Dec 2018 to Dec 2019. There will be a variety of topics, all of which involve the relationship between an area of practice or interest and the Middle Way – for example, the Middle Way and Meditation, the Middle Way and Science, the Middle Way and Judaism. This is your opportunity to find out more about a Middle Way perspective in relation to a topic that already interests you, interacting with members of the society in real time online.