Carl Jung’s Red Book contains an extraordinary personal account of engagement with archetypal figures in a series of induced visions. Robert M. Ellis, who has a forthcoming book on the subject, explains how it can also be an inspiring resource for the Middle Way. This talk was given on Zoom on 19th April 2020, as part of the Virtual Festival of the Middle Way. It is followed by questions from the audience.

Category Archives: Jung

Announcing our new webinar programme

We’ve got a new monthly webinar programme now open for booking,  running for 13 months from Dec 2018 to Dec 2019. There will be a variety of topics, all of which involve the relationship between an area of practice or interest and the Middle Way – for example, the Middle Way and Meditation, the Middle Way and Science, the Middle Way and Judaism. This is your opportunity to find out more about a Middle Way perspective in relation to a topic that already interests you, interacting with members of the society in real time online.

running for 13 months from Dec 2018 to Dec 2019. There will be a variety of topics, all of which involve the relationship between an area of practice or interest and the Middle Way – for example, the Middle Way and Meditation, the Middle Way and Science, the Middle Way and Judaism. This is your opportunity to find out more about a Middle Way perspective in relation to a topic that already interests you, interacting with members of the society in real time online.

For more information, including the full programme and how to book, please see this page.

The MWS Podcast 138: Allan Frater on Psychosynthesis

My guest today is Allan Frater, a psychotherapist and teacher at the Psychosynthesis Trust in London.

Psychosynthesis is a transpersonal or psychospiritual psychology, in which the spiritual or soulful is integrated with the psychological. It has its origins in the work of Dr Roberto Assagioli, an early pioneer of psychoanalysis which he studied under Freud and as a contemporary of Carl Jung. On returning to Italy, Assagioli went beyond psychoanalysis in the formation of psychosynthesis, which included influences from his life-long interest in eastern traditions such as Buddhism, as well as the esoteric western traditions, such as alchemy, Neo-Platonism and kabbalah.However, psychosynthesis was presented as a secular psychology and an empirical science of human subjectivity. The topic of our discussion today will be the origins, aims and methods of psychosynthesis, as well the emphasis that Allan has been developing in his teaching which he calls, ‘wild imagination’.

When we were very Jung

It was about 2 years ago now when I first read Jung’s Red Book, which had been published in 2009 after sitting unpublished for nearly a century. Although I previously had a long-standing interest in Jung, reading that extraordinary text brought me to a new level of engagement with Jungian ideas, in recognition of their potential strength of connection with the Middle Way. The first fruit of that engagement was a series of blogs (1,2,3 & 4), but then there were also new reflections on Christian symbols that contributed to The Christian Middle Way, the giving of a talk at the Bristol Jung Lectures, and also the writing of a book on the interpretation of the Red Book which I am currently trying to find a publisher for (The Jungian Middle Way). The other aspect of this engagement that I want to reflect on here, though, has been increasing engagement with Jungians. Who are the Jungians? How do they understand themselves? I’m not sure I can really answer that question, but can only give you some impressions. I’m not sure I’ve ever been quite so baffled by a group of people who in any way shelter under the same label.

There does seem to be a Jungian community – one that gathers in major cities across the Western world for talks or therapeutic training, but that also has a significant online presence. There are a number of Jungian groups on Facebook, and one of their distinguishing features is often how vast they are. The core of that community seems to consist in therapists, but there is obviously also a wider audience from a public that has been grabbed, as I was, by the Red Book, or by earlier popular Jungian writings such as ‘Man and his Symbols’ or the autobiographical ‘Memories, Dreams, Reflections’. Anyone with an imagination can be readily intrigued by Jung.

What I have found most baffling is the range of people and the range of their attitudes. This probably reflects the ambiguities in Jung himself. At his most clear and reflective, Jung is committed to writing only on the basis of experience, whether that takes the form of psychological evidence from patients or from his personal experience. He is unsurpassed, in my view, in his understanding of the meaning of that experience. At his best, he clearly separates archetypal meaning from projections of that meaning onto the world – so, for example, the Shadow is clearly an archetypal form representing our own hatred and rejection, which we should avoid projecting onto people or other entities, but rather symbolise in its own right as Satan or another evil figure (see my earlier blog on evil). In other places, however, Jung relaxes this distinction and drifts into metaphysical assertions (for example in the Gnostic Seven Sermons, near the end of the Red Book), or into groundless empirical assertions – famously including the dawn of the Age of Aquarius, and also including some very dodgy generalisations about gender, nationality and race.

Jungians, I’ve found, are similarly very varied. Some Jungians are balanced, sane, wise, thoughtful, pragmatic people whom I’ve been grateful and honoured to meet. Others are not so wise or discriminating. I am not going to mention any specific names, but here are some of the less balanced types I’ve encountered: the New Age intuitive who takes astrology seriously as a guide to the future; the spiritual intuitive who claims to just KNOW God; the obsessively rigorous scholar who won’t accept anything not clearly proved in the text of Jung’s writings; the pseudo-historian who has a detailed account of a past matriarchal civilisation that he believes could teach us all peace; and the self-appointed online authority who insists that I must be ‘overthinking’ and not using my feeling and intuition if I dare to criticise anything Jung said. Sometimes the Jungian community seems like the nearest we have to a substantial Middle Way community, but at other times it seems like a bunch of credulous hippies, and at other times a rather sinister cult.

It seems to me that perhaps the biggest issue creating this diversity, apart from the inconsistency of Jung’s own writings (and the tendency of some Jungians to absolutise them as a necessary source of truth), is the question of the status of intuition. Intuition is the means by which most of us are able to deal with complex experience readily. We ‘get the gist’ of a situation, or a perspective, or a person through a holistic overview that unconsciously draws on lots of previous experience of similar situations. Those of us who are more inclined to rely on our intuitions may thereby gain an advantage in understanding and preparedness, when compared to someone who tries to work everything out by laboriously matching concepts to what they sense. Intuition also gives us archetypal meaning by unconsciously formatting what we experience. So intuition is not flakey – it’s necessary and everyone uses it. Jung and Jungians, though, perhaps rely on it more than most as a source of insight into psychological forms and relationships.

The crucial issue is that of what intuition can justifiably tell us. On the one hand it can provide a ready access of meaning with which we can understand our experience. However, the problem with Jungianism at its flakiest is the way in which people feel they’re justified in deriving absolute facts directly from intuitions. The meaning gets translated directly into beliefs about the world without going through an intervening process of critical reflection. So that’s why we get people who believe in astrology, think they ‘just know’ God, or know the essential characteristics of, say, Germans, or women, through the operation of intuition. In the terms of Middle Way Philosophy, they are absolutising.

The research on intuition discussed by Daniel Kahneman also shows how unjustified this is. Kahneman compares studies done on the intuition of firefighters and stock traders. Experienced firefighters had excellent intuitions about when a burning building was about to collapse, because the conditions in burning buildings follow a predictable enough pattern to make unconsciously processed information reliable. However, stock traders performed worse than random when they followed their intuitions about which stocks would do best. In the past I’ve written a story about this contrast. The more complex the thing you have intuitions about, the less reliable they are, and the more important it is to slow down and actually think about it and consider the evidence.

Jungianism unfortunately has a bad reputation amongst many people who are scientifically or philosophically trained, because of this unjustifiable use of intuition to draw absolute conclusions. These hard STEM types are missing out on a good deal of very helpful material in Jungian thought. I would urge them to reconsider. But I also really wish that respect for empirical evidence was a more widespread and consistent feature of Jungian thinking than it is. You really don’t have to give up on the riches of Jungian meaning to expect adequate justification for your beliefs. You really can have your cake and eat it here. So perhaps we should all grow up.

Some other resources on Jung on this site:

Jung: Middle Way Thinkers Series

Podcast Interview with Helena Bassil-Morozow on Jungian Film Studies

Picture: Carl Jung by Charles-Henri Favrod (CCBYSA 3.0)

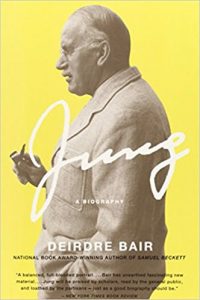

Jung and Nazism

In the aftermath of World War 2 and since, controversy has raged about Carl Jung’s attitude to Nazism, with some condemning him as a Nazi sympathiser, and others defending him in the strongest terms. After reading Deirdre Bair’s detailed biography of Jung, and following up my recent post (and as yet unpublished book) on Jung and the Middle Way, it seems increasingly clear to me that this is a classic case of a messy Middle Way strategy being misunderstood by polarised interpreters on both sides.

Jung was a citizen of Switzerland, which remained neutral throughout the Second World War. However, throughout the 1930’s he remained the president of an international psychoanalytic society that was based in, and dominated by, Germany. From the time of the rise of Hitler in 1933 this society was subject to Gleichgeschaltung, the regulations by which the Nazi government ensured conformity to Nazi values in organisations of civil society. In many ways Jung was a convenient tool for the Nazis, as they were able to use him as a source of credibility for their gleichgeschaltet version of psychoanalysis, purified of what they considered the corrupting Jewish influence of Freud with his decadent emphasis on sexuality. Although there was ambiguity in this position, because the society was formally international, the Nazis were able to manipulate that ambiguity, and he was only finally able to resign from this presidency in 1940.

It is this involvement, together with a number of incautious public statements about the psychology of races and nationalities (some of which generalised about Jewish psychology as distinct from other races) that form the basis of a case against Jung that has been raised on a number of occasions by his detractors, and even led to one (not very realistic) proposal that he be prosecuted at the Nuremberg war crime tribunals. For his critics, any compromise with Nazism or involvement in Nazi-dominated organisations makes Jung a Nazi sympathiser, and any generalisations about the psychology of Jews make him anti-Semitic.

However, Jung’s position was highly ambiguous. On his own account, his motive in remaining involved with the Nazi-dominated society was to maintain the position of psychoanalysis and to help Jewish psychoanalysts. If he had tried to take a position of purity and refused to be involved, he would have lost the possible opportunity to help psychoanalysis survive in Nazi Germany, and the opportunity to help maintain the status of persecuted Jewish psychoanalysts. After 1940, with the cohesion of the international society destroyed and Freud having fled to England, it is fairly clear that he recognised such hopes as naïve. However, he did manage one substantial achievement, which was to employ an (ironically Jewish) lawyer called Rosenbaum to introduce lots of loopholes into the anti-Semitic regulations being introduced to the society by the Matthias Goering (cousin of the more famous Goering) – who effectively developed political control over it.

As in many such highly charged and polarised political contexts, there is plenty of evidence that can be seized upon and interpreted one way, and also plenty of evidence the other way. Any case thus becomes overwhelmingly a product of confirmation bias. There is also plenty of scope for hindsight bias if we assume that the attitude Jung took to Nazism earlier in the 1930’s should have been based on their later actions – but nobody knew the full horrors to come. Highly unscientific generalisations about the psychology of races were also common currency at the time.

Later in the war, Jung also became involved in support of a plot to get Hitler overthrown, effectively providing advice about Nazi psychology to a US secret service operative working in Switzerland, as well as psychoanalytic support to a close friend who was more directly involved, both of whom were working in support of a German officer involved in a plot to overthrow Hitler. Jung’s support for anti-Nazi activities may have even gone further than this. Allen W. Dulles, the US agent mentioned, is quoted by Bair as saying “Nobody will probably ever know how much Professor Jung contributed to the Allied Cause during the war, by seeing people who were connected somehow with the other side.” Dulles went on to decline to give further detail on the grounds that most of the information was classified.

What makes me think that Jung was attempting to practise the Middle Way in any sense in this complex and ongoing situation? Partly my reading of the Red Book, which mentions the Middle Way explicitly, as I have discussed elsewhere. Partly, however, it also seems the best way of making sense of Jung’s actions. He was not ideologically motivated, though he could often be accused of political naivete. He saw the justification of one action or another in the situation, even when that situation was one dominated by Nazism, rather than solely in the terms of an ideal situation in which Nazism was not dominant. His moral values were those of individuation (as he usually called it) or what I would tend to call integration, the actual practice of which depends on the quality of judgements rather than any pre-formed general rules about the objects of those judgements.

His involvement was thus deeply messy, and he obviously left himself vulnerable to blame from both sides. It was not Nazi or Anti-Semitic, but neither was it Anti-Nazi in a way that would have made his activities less effective at the time by seeking purity from Nazism. However, it does also seem that he could have followed this path more effectively than he did: by developing more politically awareness, by seeking clearer evidence than he had before making racial generalisations, and by making the Middle Way a more explicit basis of action so as to reduce the chances of being misunderstood. Like the rest of us, however, Jung had limited knowledge, limited abilities and limited understanding with which to work, and the path of the Middle Way only requires reconciliation and adaptation to these conditions, not an unrealistic expectation of transcending them, as a basis for responsibility.

I can even find some inspiration in the way that Jung handled this difficult series of situations, not despite, but because of the many human failings that his biography has made me all too aware of. Would I, or any of us, have done better? Adopting the principle of charity seems to be the first requirement for reading the situation – a principle that allows us to appreciate the strength of messy achievement without idealising it.