A new review (by Robert M Ellis) of ‘The Runaway Species’, a lavish book on creativity by Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman, is now up on this page.

A new review (by Robert M Ellis) of ‘The Runaway Species’, a lavish book on creativity by Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman, is now up on this page.

Tag Archives: creativity

Creativity, reason and the seasons: representing autumn

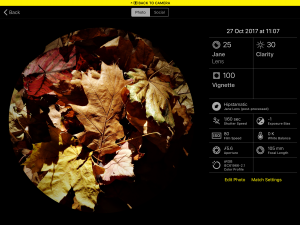

Have a good look at the photograph above. To me, it so perfectly captures what I think of as autumn. The variety of mellow colours in the fallen leaves, the gentle sunlight, the lengthening shadows. And yet the image has been carefully constructed, so as to give an impression of a natural scene that is more autumnal than anything you’ll find out there at the moment beneath the deciduous trees of the northern temperate regions. How do I know this? Because I created it.

Earlier this week, on a murky afternoon I took my son for a walk. We went to the local park and as we walked around it I carefully gathered a variety of leaves, differing in shape, size, colour and texture. He helped, with increasing enthusiasm, and seemed most amused by trying to outdo my efforts by finding leaves that were even larger than the ones that I’d found. We carried the leaves back home and I spread them out to dry. I had an idea that I would photograph them later on, but my plans were no more specific than that.

Earlier this week, on a murky afternoon I took my son for a walk. We went to the local park and as we walked around it I carefully gathered a variety of leaves, differing in shape, size, colour and texture. He helped, with increasing enthusiasm, and seemed most amused by trying to outdo my efforts by finding leaves that were even larger than the ones that I’d found. We carried the leaves back home and I spread them out to dry. I had an idea that I would photograph them later on, but my plans were no more specific than that.

On a morning a few days later I noticed that the sunlight coming in through the windows at the back of the house was particularly mellow and ‘autumnal’ – and that seemed like the right opportunity to do something with the dried leaves that were, by now, jumbled and curling inside a large shopping bag. With the help of a tripod, for stability, I photographed individual leaves lying on the sunlit floor of my back room; I photographed individual leaves back-lit by the sunlight coming in through the patio doors; finally, I heaped all the leaves on a well-lit part of the floor and took several photographs of the pile, making minor adjustments to the arrangement between exposures.

I immediately moved on to the final stage of the process – I reviewed the digital images on a larger screen, deleting some, in fact many, but retaining the others that seemed to have most ‘potential’. And then I applied some post-processing to these images, partly to compensate for the limitations of the hardware-software combinations of the camera that made the final image differ from my subjective perception of the scene as it appeared to me directly, and partly to accentuate features, textures, colour and shadow so that they were more satisfying to my aesthetic sensibility.

I immediately moved on to the final stage of the process – I reviewed the digital images on a larger screen, deleting some, in fact many, but retaining the others that seemed to have most ‘potential’. And then I applied some post-processing to these images, partly to compensate for the limitations of the hardware-software combinations of the camera that made the final image differ from my subjective perception of the scene as it appeared to me directly, and partly to accentuate features, textures, colour and shadow so that they were more satisfying to my aesthetic sensibility.

So, this morning when I was running through Southampton Common – for those not familiar with the place, it is a large public space for recreation in the city, with many paths through areas of very mature deciduous woodland – several threads of thought coincided and I realised that this photographic image that I’d made, so autumnal that it almost hurts to look at it, was a representation of nothing that could actually be found ‘out there’ in my surroundings. If a friend asked me to take them and show them where this autumnal scene lay so that they could behold it with their own eyes, I’d not be able to do this – not without reconstructing the leafy jumble on my back room floor. It would be really improbable to find the leaves from such a wide variety of tree species in one small location like this!

The creative process that led to the eventual appearance of this photograph on facebook / twitter / Instagram / flickr involved a sequence of deliberate choices, guided throughout by the idealised concept of “autumn” that I held in mind. I had chosen to go out at a particular time in the season. I selected certain leaves to make sure that I had a range of sizes, species and a progression of colours. I chose to dry the leaves (although this was partly down to convenience – I didn’t have the time to take any photographs while the leaves were still wet). I chose to photograph the leaves indoors, mainly so the wind didn’t blow them around, under very particular ‘natural’ lighting conditions. And finally, I rejected the images from the camera card that didn’t appeal to me, and digitally processed the surviving photos so that they looked the way I wanted them to.

The creative process that led to the eventual appearance of this photograph on facebook / twitter / Instagram / flickr involved a sequence of deliberate choices, guided throughout by the idealised concept of “autumn” that I held in mind. I had chosen to go out at a particular time in the season. I selected certain leaves to make sure that I had a range of sizes, species and a progression of colours. I chose to dry the leaves (although this was partly down to convenience – I didn’t have the time to take any photographs while the leaves were still wet). I chose to photograph the leaves indoors, mainly so the wind didn’t blow them around, under very particular ‘natural’ lighting conditions. And finally, I rejected the images from the camera card that didn’t appeal to me, and digitally processed the surviving photos so that they looked the way I wanted them to.

My point, I think, is that this kind of practical engagement with practising a creative art such as photography reveals a lot about what I find meaningful about the idealised concept of ‘autumn’ that I’ve created for myself. Before I’d even started this mini-project I already had an idea of what this autumnal image would look like, and the steps along the way involved continual refinement, calculated manipulation of my surroundings in order to incrementally bring my creation closer to the ideal concept that I held.

In this way, the left-brain mode of awareness, of conceptualising the world as being full of tools to be manipulated in order to produce specific outcomes, is an important part of the creative/artistic process. Dumbed-down pop psychology references to “right-brain people” being the expressive, creative, artistic ones are just that – a grossly over-simplified model. The process involves an integration of the modes of both brain hemispheres, and artistic maturity is likely to depend on the ineffable openness to experience that the right-mode provides in order to challenge the left-mode certainties that can trap us in fixed ways of seeing and thinking about our view of the world.

In this way, the left-brain mode of awareness, of conceptualising the world as being full of tools to be manipulated in order to produce specific outcomes, is an important part of the creative/artistic process. Dumbed-down pop psychology references to “right-brain people” being the expressive, creative, artistic ones are just that – a grossly over-simplified model. The process involves an integration of the modes of both brain hemispheres, and artistic maturity is likely to depend on the ineffable openness to experience that the right-mode provides in order to challenge the left-mode certainties that can trap us in fixed ways of seeing and thinking about our view of the world.

I think I’m recommending a kind of balance here, between the different hemispheric modes. Don’t be discouraged from taking part in creative and artistic practices because you don’t “have it in you”; if this sounds like you then you might make progress by understanding that creative processes require a combination of both right- and left-modes of thinking rather than it being the preserve of one brain hemisphere alone. On the other hand, if you do enthusiastically take part in creative and artistic practices, don’t repress the idea that the left-brain mode of thinking is an essential part of it all. Although it is possible to allow the reasoning, analytic side of awareness to over-dominate and perhaps derail your creative projects by bringing about too much rigidity or obsession with technical purity, but if a healthy balance is achieved then getting stuck can be avoided and new meaning and enjoyment can arise.

To conclude, I’m going to mention a different aspect of my concept of ‘autumn’, one that I have no idea yet how to express artistically. About a year ago, I was running on one of the narrow tarmac paths on Southampton Common and as I bounced along there was a continual skittering, swooshing sound following me down the path. It was the scraping of dry leaves on the tarmac, caught in the disturbed air that I left in my wake. For a few moments, before I over-thought it, I had a sense of being one moving part of the world, gently stirring other parts of the world which then danced around me. Anyway, words don’t really do justice to that subjective experience I had, so I’ll pop it on the creative back-burner and see what happens.

The act of creation

I’ve been thinking recently about creation in human experience, and also how this relates to the symbolism of creation in the Bible. I’m indebted to Iain McGilchrist here, who, in ‘The Master and his Emissary’ points out the difference between left hemisphere and right hemisphere forms of creation: I will call them reproductive and mimetic forms of creation. The more I reflect on this difference the richer it seems.

In the reproductive form of creation, some kind of idea, plan, or copy (whether mental or physical) of what is to be produced already exists. A new version of that copy is produced.

However, in the mimetic sense of creation, something already exists that may have a closer or more distant resemblance to the thing to be created: it may just be ‘raw material’ that is to be shaped, but in accordance with how it already is. The existing materials are recombined so as to produce something new that was not previously combined in that way, whether in the object itself or in the mind of the creator.

The crucial differences between these forms of creation depend on what is going on in the mind of the creator.

In the reproductive sense of creation, there are clear goals and representations of what is to be created, and the process of creation is merely to reproduce those goals as precisely as possible. The representations may or may not include an actual copy of the thing to be produced already in existence. A construction engineer building a bridge from a set of painstaking designs in creating in this sense, as is a factory production worker who merely controls a machine that is pre-set to reproduce identical plastic parts over and over again. In this sense of creation, the left hemisphere is heavily dominant.

Reproductive creation follows a positive feedback loop in which an idea is fixed on, a copy of that idea is constructed, and then the constructed thing reinforces the idea. However, reproductive creation will only actually succeed to a certain extent. The plastic parts may appear identical, but will have microscopic variations. The bridge may follow the specification as precisely as possible, but there will be at least some small divergences from it. However, the mental state accompanying this kind of creation focuses on the goal of copying, and will either be frustrated by a lack of exactness in the copying or will deny that there is any such lack, re-interpreting the creation to fit the idea and pretending in ad hoc fashion that it was intended to be like that all along. Any divergence from the plan, if it is admitted, is a failure. The view of the world adopted is one where it is assumed that it is possible to copy exactly because there is an absolute relationship between the specification and the creation. Whilst it may be admitted, on philosophical enquiry, that the copy in the plan is not exactly the same as the created thing, the reproductive creator will insist on the absoluteness of the relationship. This relationship can be called isomorphism from the Greek for ‘same shape’.

In the mimetic sense of creation, on the other hand, there is no expectation of any isomorphism between a plan or a previous model and what is created. Rather it is accepted that both the form of what is created and its meaning to us will depend on various variable factors: the nature of the materials, the mental state and expectations of the creator, or other incidental factors that contribute to what is produced. It is not that the creator will lack plans or intentions, for these will always have to be present to some extent for the activity of creation to occur at all. However, it is accepted that the creation will in some respects have a life that is independent of the creator. Different goals may emerge in the process of creation that were not envisaged at the beginning. A wider harmony and integrity will be sought for the creation which is only partially in line with any wishes the creator may have started with, also responding to the conditions that arose in the process of creation.

In contrast to the positive feedback loop involved in reproductive creation, mimetic creation involves a negative feedback loop. An idea of what is to be made is put into operation, but differences between the idea and the creation are not seen as failures, rather as new conditions to be learnt from and responded to. In this way the idea of what is being created continually changes along with the thing being created.

The mimetic sense of creation is obviously one that applies to works of art, following the senses discussed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Erich Auerbach. It also applies to parenthood – at least if it is pursued with wisdom rather than with inflexible plans for the child. Mimesis is obviously the embodied type of creativity. It is a type of creativity pursued with an active and integrated role for the right hemisphere, taking new conditions into account as well as the left hemisphere’s goals and representations. We tend to describe people as ‘creative’ who have learnt to manage the process of mimetic creation with confidence.

I don’t want to imply here that reproduction is necessarily bad: it is just limited when compared to mimesis. The problem with reproduction seems to be when it is absolutised: when we expect copies to be exact, and plans to be precisely reproducible. There are some horrendous examples in history of big plans that were put into operation with hardly any consideration for the conditions: perhaps the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme is the most astonishingly arrogant and incompetent example I have come across. Mimesis, on the other hand, is not only a quality of the best art, but also the best political proposals and the best engineering projects, among many other things.

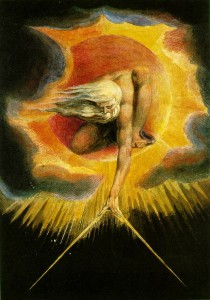

If you apply these ideas about Creation to God’s creation of the world in Genesis, they can be related to the debate about what sort of creation Genesis is describing. Did God simply have a plan that he put into operation regardless? If so, we could read the Creation story as a left hemisphere fantasy of the total and precise enactment of a plan, based on total power. This way of thinking seems to be implied in the classic Christian interpretation of the Creation as ex nihilo – that is, as creating something out of nothing. Blake’s famous ‘Ancient of Days’ picture depicts this kind of creation.

But the text begins “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was a vast waste, darkness covered the deep, and the spirit of God hovered over the surface of the water.” (Gen 1:1-2), which can on the contrary be read as indicating that earth, ‘the deep’ and water already existed, and were merely formed by God. This interpretation would fit the influence of Babylonian and other near eastern creation stories on this one, as the other stories all involve prior existent matter.

If we try to let go of all the metaphysical claims and associations with Christian (and Jewish) dogmas in the Genesis story, we can read it archetypally and in accordance with human experience, simply as an inspiring symbol of creativity, with an archetypal God as a cosmic artist. God does have plans, but he also has raw materials and unexpected conditions to respond to. He pauses each day after making each new set of things before continuing, suggesting that he wasn’t just putting his plans into operation without reflection. What’s more, if you’re creating something as complex as life, you must expect it to respond in unexpected ways: as Adam and Eve are depicted as doing. For more on the Eden story, see my previous post, ‘Reconsidering the Fall’ (and also don’t miss Emilie Aberg’s excellent comment on that).