Should the concept of adaptivity (or adaptiveness) not itself be adaptive? In my work on Middle Way Philosophy, I’ve often found myself arguing that a traditional way of thinking about a concept that may have worked in a past context is too restrictive for the present one. Moving on from the limitations of Buddhist ways of thinking of the Middle Way as lying between ‘eternalism’ and ‘nihilism’ is one example of this, and another (that I’m working on for my next book) is the need to move on from Jungian accounts of archetypes as innate features of the ‘collective unconscious’. In both cases, the alternative needs to be a more universal and thoroughly functional account of the concept, helpful to all people in all places rather than tied to a limiting paradigm. We owe a huge debt to the people who developed these concepts, but need to pass on the flame rather than worshipping the conceptual ashes. So it seems, also, with the concept of adaptivity itself, which for many people is strongly tied to a Darwinian paradigm.

In the basic Darwinian view, adaptivity is a matter of the continuing survival and reproduction of an organism in changing conditions. The organism passes on its genes to its descendants with minor mutations, some of which are better adapted to new conditions and others of which are not. ‘Natural selection’ then ensures that the better adapted organisms survive and reproduce, whilst the less well adapted die out. This kind of adaptivity , however, is a relatively crude. It takes a very long time for significant adaptation to occur, only operates at the level of entire species or sub-species, and requires the maladapted to perish in the process. Nevertheless, many thinkers still seem to think of this as the only acceptable understanding of adaptivity. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, for instance, expresses a valuable perspective on the long-term value of our ability to adapt to extreme and unpredictable events, or ‘fat tails’ as he calls them. If our perspective is too short-term, and we fail to take these events into account, even if we appear to be well-adapted to a more limited immediate range of conditions, we lose. However, the kind of adaptiveness he has in mind appears to be only that of survival (even if not strictly only of a species). In this he seems to follow a strand of thinking in evolutionary biology that reduces all other forms of adaptation to that one.

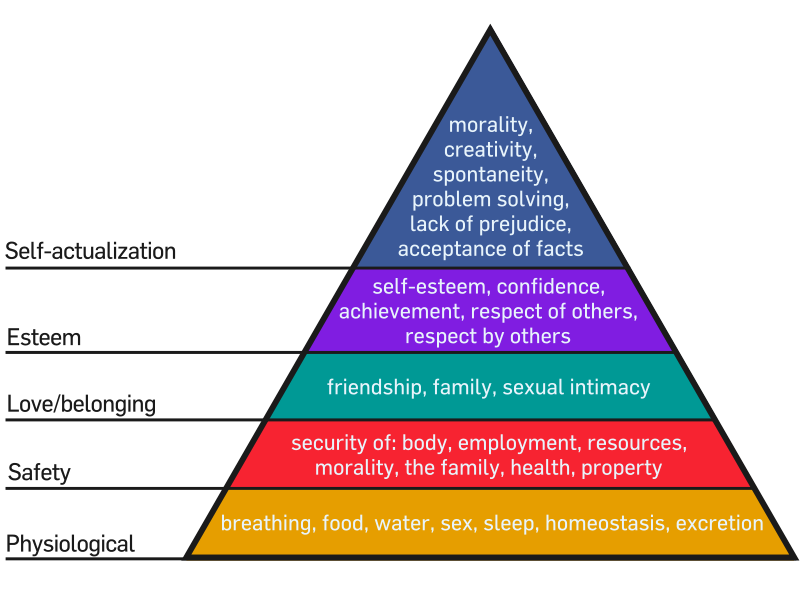

However, adaptation is clearly a much more complex concept than that. It is a feature of a system, and systems may operate at different levels where their goals may not be just the survival of the system (practically necessary though that remains), but rather the fulfilment of a variety of needs. As systems evolve greater complexity, their goals also become more complex. Whilst survival is always the grounding condition on which the development of other goals depends, a hierarchy of ‘higher’ goals can develop in dependence on them. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs expresses those adaptive goals for humans, working up from the social adaptations of belonging and esteem to the individual one of what Maslow called ‘self-actualisation’. But how can we understand Maslow’s insights in the context of adaptation? After all, a reductive evolutionary biologist would probably say that all of these needs boil down to survival in the end, and that even self-actualisation is only adaptive because it helps us solve problems or get on with others in ways that help us survive. I don’t agree that that’s the whole story, though, and it has recently occurred to me that talking in terms of a fractal structure may help to explain the relationships between different types of adaptivity. In a fractal structure, the features of a larger system are reproduced (potentially infinitely) at smaller and smaller scales, the Mandelbrot Set (pictured) being an example of th

But how can we understand Maslow’s insights in the context of adaptation? After all, a reductive evolutionary biologist would probably say that all of these needs boil down to survival in the end, and that even self-actualisation is only adaptive because it helps us solve problems or get on with others in ways that help us survive. I don’t agree that that’s the whole story, though, and it has recently occurred to me that talking in terms of a fractal structure may help to explain the relationships between different types of adaptivity. In a fractal structure, the features of a larger system are reproduced (potentially infinitely) at smaller and smaller scales, the Mandelbrot Set (pictured) being an example of th ese relationships mathematically turned into an image.

ese relationships mathematically turned into an image.

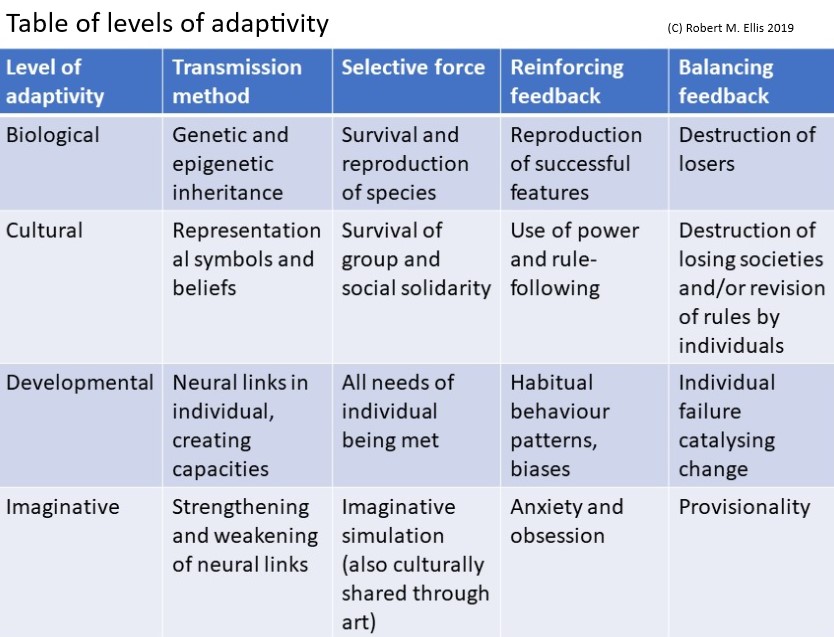

To think of adaptivity in a fractal way, we’ll need to think of a hierarchy of successively smaller systems (smaller both in time and space) dependent on the larger one, but in which the same basic pattern of conditions operates. Exactly how you divide up levels of adaptivity may be a matter of debate, but I think we can distinguish at least four levels: biological, cultural, individual and imaginative. In each case there is a means of transmission of certain features that operates only at that level, a specific selective force that depends on the fulfilment of needs in different conditions, and both reinforcing and balancing types of feedback. I’ve suggested what the features of these four levels might be in the table below, though I’m sure this sketch can be refined.

When we get to the ‘higher’, or more distinctively human, forms of adaptivity, it is our use of symbols to create meaning that seems to be the basis of adaptivity, but operating in three different ways. At a cultural or social level, shared symbols and beliefs help societies to adapt, although rigidity in those symbols and beliefs can also become maladaptive. At this level, safety, belonging and respect start to become important in addition to survival. At an individual level, the development of an individual capacity for meaning and belief through neural links allows that individual to meet all their needs, including self-actualisation. Again, however, rigidity of belief can be maladaptive – this time for the individual. Within the individual, and within a shorter time-frame rather than a whole life, there is finally an imaginative level of adaptivity that is created by our ability to use symbols hypothetically and thus simulate possibilities in our minds. This imaginative process boosts our adaptivity as individuals, helping us to adapt far more quickly than we could do by merely waiting for our previous habits to fail us in new conditions. However, once again, maladaptivity for the individual occurs through the reinforcing feedback of imaginative reconstruction in loops of anxiety or obsession.

I think that these ways of understanding adaptivity help us to distinguish the Middle Way clearly from other kinds of adaptivity to a context. The practice of the Middle Way does not consist in just any kind of balancing feedback loop, but rather the development of awareness required for provisionality. If we can examine alternatives hypothetically, we can not only be freed from reinforcing feedback at the imaginative level, but also start to make an impression on the more basic levels. Provisionality applied consistently and courageously can change both long-term individual development and social beliefs, slow and frustrating though that process may seem when we see our societies going through damaging reinforcing feedback loops. Whether we can successfully influence the biological level is much more debatable.

However refined our thinking as individuals, however, we are still subject to the more basic conditioning of the biological level. As we are increasingly discovering through the climate crisis, the very existence of the more complex and refined systems, both social and individual, is under threat if we cannot maintain the basic conditions for our survival as a species.

Pictures: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs by factoryjoe (Wikimedia Commons). Mandelbrot Set picture of unknown origin. Table of levels of adaptivity by the author.