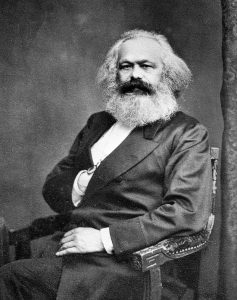

In recent weeks I have been hacking my way through piles of exam papers, particularly featuring a question about Marx. Although this activity generally requires the suppression of all creative impulses in favour of total concentration, I still haven’t managed to stop myself engaging in some reflections about the relevance or otherwise of Marx’s beliefs about class struggle today, and how it all relates to the Middle Way. Now that I’ve finished the marking, I’m finally at sufficient liberty to write down my thoughts.

In ‘The Communist Manifesto’, Marx and Engels famously described the whole of human history as a history of class struggle. In one way or another, they say, the propertied classes have constantly found new ways of exploiting the unpropertied proletariat, in differing circumstances from ancient slavery to the factory floor. However, they go on, capitalism creates such extreme exploitation that eventually the workers “will have nothing to lose but their chains”. Purified by their total exploitation, they will overthrow the bourgeoisie in a revolution, which will usher in a merely temporary dictatorship of the proletariat, followed by the ultimate stability of the communist society.

The elements of dogma in this story are not too hard to identify. The socio-economic determinism is one: Marx’s ‘inevitable’ story shows no signs of turning out quite like that. The purification of the proletariat through suffering is also a projection that seems to have no basis in psychological, let alone historical, conditions. Far from gaining the ultimate wisdom to finally end social and political conflict, people who are suffering acutely tend to get more stressed and more reactive. It’s only if you are very well prepared for your suffering that you might be able to learn from it, but even then it’s unlikely to bring you to an absolute state of moral perfection.

Nevertheless, the power in Marx’s story, fuelling several revolutions, also suggests to me that there must be some insights in it, mixed in with the dogmas. The story that history is a matter of class struggle does seem potent, because it is indeed quite possible to analyse history in that way. More profoundly, though, class struggles are also struggles within individuals, who identify with different sets of beliefs that may either prioritise narrow economic interests or wider values. Those conflicting values also defy resolution because they are framed in absolute terms. When you feel that you have to choose between your job and your conscience, for instance, that is ‘class struggle’ in a the wider sense, whether you are a nineteenth century mill worker or a modern Conservative Member of Parliament. You can focus on class struggle sociologically and ignore the psychology (as Marx did), or you can focus on resolving the psychology of the personal struggle and ignore its political dimension (as in the recent phenomenon of ‘McMindfulness’), but the phenomena you are dealing will have all these dimensions, and the tendency to ignore some of them is an unfortunate result of over-specialisation.

Property can provide powerful vested interests, but vested interest is not the only human motivation, so I cannot agree with Marx’s assumption that the story of class conflict is only about the division between those who have property and those who do not. Instead, it seems to me more powerfully to be between those who absolutise narrow motives (including, but not limited to, property interests) and those who, whilst remaining human and having interests, are capable of thinking provisionally about them and weighing up different values. Ironically enough, those who are capable of doing this quite often have a modest amount of property, which has given them enough security to be able to start thinking provisionally. Those who have no property at all are often (but not always) so insecure that it’s difficult for them to avoid thinking in absolute ways that are constantly fuelled by craving and anxiety. No, the proletariat are not purified by their suffering. Rather their suffering makes them easier for unscrupulous absolutists to exploit.

So what is the class struggle today? Well, we are in the midst of it. The US and the UK particularly are currently wracked by political conflict that seems to have a strong class basis. That political conflict involves ongoing polarised disagreement about climate change, about nationalism, about social justice, about the rights of minorities, and about the role of the state, along with many other associated issues. It’s not a conflict between the property-owning bourgeoisie and the propertyless proletariat though. Rather it’s primarily a conflict between, on the one hand, a cabal of autocrats and billionaires with their numerous stooges, and on the other, middle class intellectuals. Not all members of any particular socio-economic group are necessarily on one side or the other – there are still middle class intellectual climate change denialists, working class internationalists, and billionaire liberals. Nevertheless, the conflicts have a strong class dimension as well as a psychological and philosophical dimension. It would be surprising if they didn’t, given how important social class is to our identity.

The ‘middle class intellectual’ class has not been merely created by material conditions and accompanying vested interests, as Marx would tell us. Rather, they have come to appreciate conditions better, and overcome some of their biases, by having their minds opened in one of a variety of possible ways. University education and professional training provide the most common vectors for it (as shown in Robert Kegan’s work on the contexts for what he calls stage 4 and 5 adult psychological development). Travel, friendship, study, art, and religious experience all provide other possible routes to bigger perspectives that may help to inoculate you against becoming a stooge.

The new propertied exploiters, on the other hand, are defined either by their narrow focus on power and economic advantage, or by other dominant absolute beliefs that facilitate that exploitation (such as religious fundamentalism). The majority of their supporters, though, are subject to what Marx called ‘false consciousness’: that is, they have been influenced into a set of beliefs that are against their own long-term best interests. The sources of false consciousness now come overwhelmingly from media manipulation that can apparently be traced back to autocrats and billionaires, from Fox News to the Daily Mail to Russian troll factories. This media bias chart provides a useful reference of the sources of such manipulation (which are found on left as well as right, but are overwhelmingly weighted towards the right). The strong links between climate change denial, the fossil fuel industry, and right wing politics are also confirmed by a number of academic studies.

In Marx’s analysis, intractable class conflict can come to an end only through violent revolution that breaks the mould of the system. Unfortunately this seems to be another of his delusions, if the evidence of actual revolutions is anything to go by. A revolution may change those in power, but it is unlikely to change the systemic patterns of interaction, which are likely to reassert themselves to a greater or lesser degree (as they did in the Soviet Union). The stakes in our new class conflict, though, are far higher than just the exploitation of one class. The very survival of human civilisation is at stake. The conflict may end in the ‘revolution’ of the destruction of all, or it may be gradually ameliorated through changes in the ways that we respond to conditions. Either way, though, the middle-class intellectuals will evidently prevail in the long-run, just as Marx predicted that the proletariat would prevail, either by being proved right or by running the world their way. That’s not because they’ve been purified or because their perspective is perfect, but rather because they imperfectly recognise that their perspective is imperfect when their opponents do not.

Is this another story as incredible as Marx’s? I think it identifies some of Marx’s insights (class conflict, its intractability, its relationship to ideology, its asymmetry, and the nature of false consciousness) whilst also drawing attention to his dogmas (determinism, absolutisation of vested interest, purification of suffering) and limitations (ignorance of psychology, ignorance of ecology). Marx was concerned, most basically, with how people address conditions, but the ‘science’ with which he interpreted this was heavily loaded with false assumptions. The updated story I’m offering in its place may also be based on some false assumptions, but at least it is based to some degree of recognition of the need to address such assumptions (Marx tended, instead, to say that his story was ‘science’ and everyone else’s was ‘ideology’).

I expect some of the first reactions to that alternative story to be based on false equivalence, which is a common absolutist strategy (think of Trump drawing equivalences between white supremacist demonstrators and their opponents). For an absolutist, everything is dual, and there can be no such thing as better judgement through provisionality. Their opponents are therefore always assumed to be as absolute as they are, and they will insist on reducing all complexity to that equivalence. Incremental marks of credibility (such as expertise, relative lack of vested interest, ability to observe, and corroboration) as well as every kind of evidence and every widely-used value, are ground down by absolutists into the same false equivalence. However, as Marx recognised, the class struggle is asymmetrical. One side is right and the other wrong (even if it’s not always clear who is on each side), because the wrong side is entirely blinded by its assumptions, totally immersed in confirmation bias. We are all subject to confirmation bias, but some of us are facing up to this fact and others are not.

The other objection I am expecting will be to point out a false dichotomy. “It’s not as simple as that,” you may say. “Surely there were not just two conflicting classes in Marx’s day, and there aren’t now either?” I agree. I am only trying to make sense of the idea of “class conflict” by separating out the elements that seem to demonstrably cause conflict from those that are just Marxian dogmas. However, any generalisations we make about “classes”, especially when they involve determinately dividing people up, are fraught with all kinds of complex difficulties. That’s why I only want to define the “classes” in terms of their relationships to absolutisation. Whenever you or I are dominated by absolutisation, we’re in the repressive class, as exploiters or their stooges, even if we’re middle-class intellectuals. If we cease to do so and start to judge provisionally, even if we’re in the pay of Fox News, we cease at least temporarily to be in that exploitative class. We cannot define the classes sociologically in any way that I find remotely satisfactory. The social categories I have used above can only be proxies for psychological ones, and are just ways of pointing out that the psychological conditions do have constant social implications.

Psychologically, too, absolutism is not defined by counter-absolutism, but by its own assumptions. Once again, then, we also see that the Middle Way is not a compromise. If we respond to absolutists with counter-absolutism (as some left-wing absolutists do) we become absolutists. However, if we respond critically but with confident provisionality, we are not being dogmatic. The practice of the Middle Way is provisionality, not compromise, and the confidence with which it needs to be taken up must not be automatically mistaken for dogma. The Middle Way seems to be the only practical solution to the class conflict that so much concerned Marx.