The latest film from Martin Scorsese, now in cinemas, is entitled ‘Silence’, and concerns the struggles of Jesuit missionaries in a nascent Christian community in seventeenth century Japan. It’s a harrowing film to watch, because it contains a great many scenes of gruesome torture inflicted by the Buddhist Inquisitor on Japanese Christians and missionaries to get them to apostasize their beliefs, but it’s also a film that I felt raised troubling questions about how we should treat our identities and commitments. Should we be prepared to renounce them to save our lives? For someone of Christian identity, is stepping on an image of Christ just a formal gesture of no great significance, as the wily inquisitor urged? Or is it, simply by yielding to power and surrendering the individual conscience, a deeply undermining act, compared to which martyrdom might even be preferable?

This film depicts a world that is a long way from any obvious application of the Middle Way – a deeply polarised world of clashing absolute beliefs. After initially tolerating limited European influence, at this stage the Japanese government had entered a phase of isolationism during which they were determined to limit foreign religious influence as well as other kinds of political influence, by any means necessary. Christian villagers are depicted as being crucified, ‘baptised’ with boiling water, summarily decapitated, drowned, or hung upside down in a pit with their neck veins opened, to induce renunciation either from them or from equally unfortunate missionary spectators. Ironically, of course, the Buddhist torture being inflicted on religious minorities in Japan mirrors the equally gruesome and better-known torture inflicted by the Catholic Inquisition on any type of heresy in Europe, at the very same time.

[The remainder of this review contains plot spoilers.]

But many people have lived in such a desperately polarised world, and indeed still do so. The Middle Way should still be practicable in such a world, as it should be in any conditions, but what does it imply? On the whole I found my sympathies with the character of Father Ferreira, an earlier Jesuit missionary who is depicted as having renounced his faith under earlier torture and to be living in Japan and studying Japanese thought. Ferreira urges the younger Jesuit who has come to find him (Rodriguez) to renounce similarly, rather than waiting for Japanese Christians to be tortured to death one by one in front of him. Ferreira recognises that the religious meaning of Christ and of Christian commitment to him is not just a matter of tribal identity, and insists that the loving action in the circumstances is to yield. After a great deal of resistance, Rodriguez finally convinces himself that Christ would understand his action, and apostasizes. In effect, Ferreira recognises the unhelpfulness of absolutizing religious commitment and confusing it with tribal identity. He seems to have made a step in the direction of the Middle Way, by allowing new information from outside to soften his previously rigid beliefs.

However, this also didn’t seem to me to be such an obviously right judgement, because of its political effects. If the state or a religious authority uses absolute power in this way, yielding to it could also be seen as encouraging that type of policy. Defying it, on the other hand, could possibly have the effect of encouraging tolerance. In the circumstances, though, the prospects of changing Japanese policy through defiance would seem to have been pretty remote. Much longer-term social and political change was required to eventually open up Japan. So I continue to see Ferreira as more justified on the whole, though with a full acceptance of the limitations of any judgement I can make from my comfortable armchair in relatively tolerant 21st century Britain.

However, I doubt if this is Scorsese’s own view. In the very final scene, we see Rodriguez’s burial according to Buddhist rites, with any indications of the deceased’s Christian origins strictly forbidden: but Rodriguez is clutching a hidden cross which his wife has presumably planted in his cupped hands. At the beginning of the final credits, there is also a dedication to the martyred Japanese Christians, ‘ad majoram dei gloriam’. Scorsese, as a Catholic, seems to want this in the end to be a triumphalist film about Christian heroism in the face of Buddhist oppression, despite the deep ambiguity of most of the film. I felt this was an artistic betrayal of the more creative ambiguity that the film would have done better to stick with.

Critics have been lambasting the film for being too long – the trademark criticism of an impatient age. I didn’t find it too long, but I did sometimes feel that the torture scenes were overdone. Despite these limitations, it is still a film well worth seeing for anyone interested in confronting the full anguish of our religious past. Although Scorsese’s artistic instincts seem to be in conflict with his dogmatism, most of the time the artistic instincts win out.

I’d especially recommend this film for any Buddhists who are inclined to idealise their religion by considering it intrinsically different from any other in the mix of its historical attitudes to violence and oppression. For example, Sangharakshita wrote:

Not a single page of Buddhist history has ever been lurid with the light of inquisitorial fires, or darkened with the smoke of heretic and heathen cities ablaze, or red with the blood of the guiltless victims of religious hatred. Like the Bodhisattva Manjushri, Buddhism wields only one sword, the Sword of Wisdom, and recognises only one enemy – Ignorance. That is the testimony of history, and is not to be gainsaid[1].

Such completely inaccurate idealisations are unfortunately still found amongst Western Buddhists, together with the assumption that the conceptual content of your metaphysical beliefs somehow makes a difference as to how rigid they are and how much conflict and oppression they create. But it’s not whether you call your ideal ‘God’ or ‘Enlightenment’ that makes the difference here, but whether you absolutise it. Scorsese’s film has the merit of making this point abundantly clear.

[1] Sangharakshita, Buddhism in the Modern World

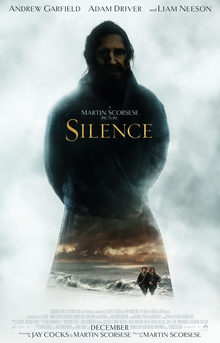

Picture: film poster copyright to the film-maker/distributor but copied from Wikipedia under fair use criterion. Please see this link for fair use justification.