“We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor all logic, but is somewhat beauty and poetry.” Maria Mitchell, astronomer, first female member of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences (quote and picture from Geozilla)

Science has a problem. For all it’s wonderful, bewildering and sometimes terrifying discoveries (discoveries that have shaped the world that we live in, as nothing before has) science is treated with contempt and mistrust while at the same time (and often from the same source) being worshipped as the miraculous and supremely authoritative fruits of superhuman individuals – ruthless rationalists, seemingly void of normal human responses. There are countless examples of this, from the MMR scandal and the climate change debate to the seemingly daily claims of cancer cures that adorn the front pages of our favourite tabloids (one would be forgiven for wondering how it is possible that anybody could even develop cancer any more)! My suspicion is that the problem is borne and perpetuated throughout society, from schools and media to the scientific community itself.

I am not a scientist, most of my understanding of science comes from reading populist science books and so I offer no authority on the nuances of the scientific method. My intention here is not to suggest possible alternatives to any part of the scientific process, suffice to say there are many dissenting voices and my guess is that any major shift will come – as it has in the past – from within the community itself. What I will attempt here is to explore the perception of science, as it is presented and understood by what I believe is a large proportion of the population, whilst simultaneously suggesting a more objective (in the Middle Way sense of the word) model, that I hope will avoid dogma, still allow and possibly assist – science to continue doing what it does best.

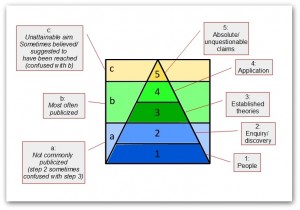

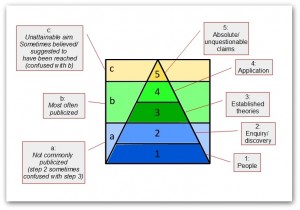

I have broken the process of science into five incremental stages, which can be put into three distinct groups of differing levels of public perception. As can be seen in the  diagram provided, the stages (which are numbered 1 – 5) form a triangle which rises up through the levels of perception (lettered a, b, c).

diagram provided, the stages (which are numbered 1 – 5) form a triangle which rises up through the levels of perception (lettered a, b, c).

Level-a:

This level contains the first stages of the scientific process, which are rarely publicized and are little understood by much of the public (Michael Brooks claims that this is how many scientists wish it to remain).

Stage 1 – People

Science, like art, begins with human beings, and scientists, like artists, are not only capable of wondrous creative leaps but also of jealousy, dishonesty, romance, delusion, dogma and the whole spectrum of human vices and virtues. Yet the public perception of scientists seems to be of robot like boffin’s, working together with ruthless rationality and poise. While science appears to maintain a dogmatic status-quo that is beyond challenge, individual scientist must be as competitive and ambitious as the rest of society. While the established order jealously guard their hard won theories, the young upstarts must surely be desperate to instigate revolution. These revolutions do happen, but they are rare and require exceptional creativity. Relativity, The Big Bang Theory and Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle all turned contemporary scientific thought upside down – their instigators all challenged the institution, and won. To the scientist that proves that the speed of light is not the universal speed limit – a Nobel prize, world fame and the drinks are on you!

It is easy to stereotype scientists in the way that I have described above, or indeed as wild haired genius’s, but the reality must surely be more balanced. Scientists come in all flavours which means that they can hold differing philosophies and have conflicting religious beliefs, enabling them to tackle problems from alternative points of view – which can only have a positive effect on the process of scientific endeavour.

Stage 2 – Enquiry/ Discovery

Much of this has been covered above, although not all scientific enquiry can result in the revision of commonly held thought. Most of it is likely to be relatively mundane and most of it is also likely to be unsuccessful – in that results will be negative. Nevertheless, it is at this stage that individuals and groups can really let their creativity and imagination go wild and this is where the maverick has a chance to shine. It is worthy of note that the three theories that I cite above, most likely started life as ‘wacky’ ideas that were rejected by much the scientific community. The majority of fringe hypotheses and unconventional theories are likely to fail, but their exploration should still be encouraged. It is from here that the next major advancement is likely to come.

Level – b:

It is this level that I believe is the most visible, and it is these stages that many people seem to regard as ‘science’. Again, Michael Brooks argues that many scientists want it to stay that way.

Stage 3 – Established Theories

This stage really represents the current scientific thought of any given time. It is this thought that is often presented, in schools, the media and elsewhere, as unquestionable fact (which is actually stage 5). In the scientific sense this is where the facts are, but this word causes problems and is misused by scientists as well as non-scientists. The word ‘fact’ in this context should always be accompanied by a ‘with our current understanding’, which in most cases it (sometimes silently) is – even if it is only lip service, paid by a seemingly dogmatic individual.

That there can never be any fact that is 100% validated is a reality that is often exploited by those that wish to challenge current scientific thinking, and this can have serious consequences. Climate change is a good example. When ever a scientist makes a prediction, there is always an element of doubt, and sometimes these predictions prove to be wrong or inaccurate. From a scientific point of view this is fine, but this inherent uncertainty enables those that have conflicting agendas to exaggerate the margin of error to devastating effect. The same tactics are also employed in the creation/ evolution debate.

While it seems to me that stages 2 & 3 must directly inform each other (in a kind of feedback loop), it is important that they remain separate in terms of advancement to level 4. Challenges to any scientific theory should be encouraged, but those challenges that determine or alter the application of science, without the appropriate evidence must be treated with caution.

Stage 4 – Application

This is where established theory is employed for practical purposes. Our whole society can seem like it is the result of stage 4. There are bridges, aeroplanes, computers, electricity, medicines, films, recorded music – the list is endless. For many, this is science; putting a man on the moon and microchips – but this is only the result of a long, and (despite my simplification) complex process. Many people expect science to be useful, and it often is, but that is missing the point. Science should come from a curiosity of the universe that we live in. Many theories never have a practical application, or at least don’t during the lifetimes of those that discover them, and that is fine.

Stage 4, although often the accumulation of the stages that precede, is no more important and a scientific journey should not always be expected to arrive at this destination – even though it can obviously be worth it when it does. Additionally, It should be noted that not every application of scientific discovery is always desirable!

Level – c:

Although this level can never be reached, claims are sometimes made, or misunderstood to have been made that would fit here, and for some this is where science already resides. This level can often be confused with, or thought to be a part of, level – b.

Stage 5 – Absolute/ Unquestionable Claims

Stage 5 represents the logical conclusion of any scientific exercise, which is to fully understand the universe, even though this aim is unachievable. While it is regarded as an unattainable ideal, of which the journey towards is worthy in itself, it can be useful as a point of focus. Nonetheless, it can be problematic, especially where it is claimed that a final and unquestionable truth exists. I would suggest that in many cases, where it appears there is a claim that would be at home in stage 5, there has actually been a misunderstanding that has resulted from the language used to describe claims in stage 3. The speed of light is a good example of this.

One can often hear scientists saying that it is impossible for anything in the universe to exceed the speed of light, and this sounds very much like an absolute claim. At school it is taught as such and the media treat it as such, they are mistakenly presenting it as a stage 5 claim. However, when a scientist makes this claim there is, in most cases, the additional ‘given our current understanding’ and ‘if you are suggesting otherwise then show me the evidence’, the problem is that these are usually presumed, and therefore unspoken statements.

As human beings, there are undoubtedly individual scientists that believe that some of the claims of science have reached stage 5, but as long as science in general does not then I do not see this as much of an issue. Some scientists also believe in God while others don’t – which similarly does not cause me concern.

From the perspective of the Middle Way I think that it is important to view science as a whole, which along with the arts and philosophy forms part of an even greater whole. I think that when one places too much focus on any individual stage then misunderstanding will arise and science will suffer. The only stage that I am unsure of is number 5, for me it is fine as a motivating but unobtainable goal, but I suspect that others might differ in this.

Level – c (stage 5) aside, the current trend of focusing mainly on level – b should be disregarded, and I would like to see levels a and b combined, which a Middle Way perspective should achieve with little effort. Of course for the early stages to be better understood they need to be much more visible, and this will ultimately come down to the efforts of the education system, the media and the scientists themselves.

This is clearly a simplified model. In reality there is much overlap between the stages and the order is not set in stone – as I mentioned above there is an obvious feedback loop in effect between levels 2 and 3. I have also negated to mention the ethics of science, which is already an ongoing debate. Some seem to believe that ethics only exist in the application of science, but I would suggest that the reality is much more complex. Ethical considerations, in varying forms (owing to stage 1), seem likely to exist and to play an active role at every stage of the process – perhaps this is something that the Middle Way Society can explore in greater detail at a later time.

There are bound to be errors here, both in my understanding of science and my application of the Middle Way to it , and I accept that I may have missed my target. As yet I have not discussed or shown these ideas to anybody but I hope that, if they are not as complete as they seem to me at the time of writing, they might still form part of a wider discussion about how the Middle Way Society might approach science and scientific issues in the future.

The rider thinks he’s in charge, but most of the time he’s just pretending to direct an elephant that is going where it wants to go. He gives lots of psychological evidence for the extent to which we rationalise things we’ve already judged, rather than making decisions on the basis of reasoning. This is the whole field of cognitive bias. For example, people experiencing a bad smell are more likely to make negative judgements, and judges grant fewer parole applications when they’re tired in the afternoon than they do when they’re fresh in the morning.

The rider thinks he’s in charge, but most of the time he’s just pretending to direct an elephant that is going where it wants to go. He gives lots of psychological evidence for the extent to which we rationalise things we’ve already judged, rather than making decisions on the basis of reasoning. This is the whole field of cognitive bias. For example, people experiencing a bad smell are more likely to make negative judgements, and judges grant fewer parole applications when they’re tired in the afternoon than they do when they’re fresh in the morning.