A new series of real-time online discussion groups using Skype begins from 21st Sept. This series will be led by Robert M Ellis, and based around the introductory book ‘Migglism’. Please see the Online Discussion Groups page for details, and submit the online form if you would like to participate.

Monthly Archives: August 2014

The MWS Podcast 33: Iain McGilchrist on Dogma and the Brain

In the first of a series of regular dialogues with thinkers on various subjects, the chair of the society Robert M. Ellis discusses dogma and the brain with psychiatrist , author and patron of the Middle Way Society Iain McGilchrist.

MWS Podcast 33: Iain McGilchrist as audio only:

Download audio: MWS_Podcast_33_Iain_McGilchrist

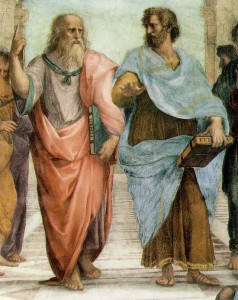

The quarrel between philosophy and poetry

‘”The part which relies on measurement and calculation must be the best part of us…. So is not the part which contradicts them an inferior one?”

“Inevitably”‘ (Plato’s Republic, 603a)

Thus does Plato provide the basic rationale for his condemnation of poetry, along with the other arts. He says that the works of the poet, like those of the artist, have “a low degree of truth” and “he deals with a low element of the mind”. “We are therefore quite right to refuse to admit him to a properly run state” continues Socrates, in pronouncements that are only echoed and accepted by others in the dialogue. Thus begins the long quarrel between philosophy and poetry.

It is easy to see this quarrel as reflecting that between those who judge solely on the basis of the representations of the left brain hemisphere at a particular time, and those who, using the right hemisphere, want to look beyond such certainties and integrate the contents of the left hemisphere at different times. Plato, through the mouthpiece of his dramatised Socrates, appears to reflect that left brain certainty: that rightness dwells only in the apparent clarity of our current representation, and in its tools of positive measurement, critical analysis, and planning. Humour, ambiguity, and grief should not be publicly shared in art, he says, but rather repressed and made objects of shame, made subject to the control of ‘reason’.

Fortunately, Plato’s ideal Republic of the left brain was never created in the fashion he envisaged it. However, he has had many imitators, particularly in the shape of political revolutionaries of a kind who wished to purge the world of all untidy ambiguity that did not fit their utopian vision. Rather than keeping them out of the Republic entirely, the Fascist and Communist regimes of the twentieth century subjected poets and other artists to censorship and control, so that they could only publicly express what fitted the party line.

Plato attacked poetry because he believed it was a form of rhetoric, which would stir up and manipulate uncontrolled emotions, but ironically it is philosophy that has too often become allied to rhetoric by offering naïve political schemes or supporting conventional views of the world, at odds with the immediacy of poetry. It is the poets who have generally understood rather better that meaning resides, not in representations, but in embodied experience. Language that does not speak to that experience appeals only to the shared lowest common denominator of human experience. Without poetry we are too often left to the clichés of the crowd and its groupthink, unable to summon creative responses to new conditions because the very tools of our thinking have been blunted by the platitudes of conventional certainty.

I have recently come across a quotation from the great Irish poet W.B. Yeats that gives wonderful expression to this poetic counter-attack:

“Ideas and images which have to be understood and loved by large numbers of people, must appeal to no rich personal experience, no patience of study, no delicacy of sense…. Manner and matter will be rhetorical, conventional, sentimental; and language, because it is carried beyond life perpetually, will be as wasted as the thought, with unmeaning pedantries and silences, and a dread of all that has salt and savour.” (from J.M.Synge and the Ireland of his time, 1910, quoted recently in a TLS article by Roy Foster)

Of course, philosophy is a varied thing, but if modern philosophy has a consistent theme (with only a few exceptions) it is the overwhelming dominance of limited, ‘flat’ left hemisphere thought in which the wider use of thinking in experience is completely ignored. In the case of Anglo-Saxon philosophy, it may be precise, analytic and highly technical, but nevertheless have the effect only of reinforcing conventional attitudes, or (in the case of post-modernism) it may be highly critical of all conventions, but again in a decontextualized way that gives no attention to the depth or breadth of experience or the practical context in which it is read. Whilst this kind of philosophy may seem of marginal interest to most people in modern society, that marginality might be seen as the unintended and ironic outcome of Plato’s approach. By relying entirely on an inadequate conception of ‘reason’, philosophy has made itself marginal. However, the conventionality, parochialism, cynicism and relativism that dominate it are shared with much of the rest of society.

Has either side ‘won’ the debate? On the one hand it seems that philosophy has ‘won’ in the sense that poetry is extremely marginal in our society, and superficial representationalism rules supreme. On the other hand, however, it seems that poetry has ‘won’, because it has not been banished from the state, and every new generation finds new ways of connecting with the imagination, however puritanical the public discourse. It is, of course, an unwinnable war and a delusory conflict, because both philosophy and poetry address central areas of human experience. Every time we machine-gun down the ‘opposition’, it is likely to pop up again, like an army of indestructible revenants.

It’s time for a new attempt at lasting peace negotiations. Part of a lasting solution, in my view, involves the deconstruction of the wrong assumptions on which the whole conflict has been based. No helpful philosophy can be assembled on the basis of a representational view of meaning that denies the body and its shaping effect on even the most abstract of our constructions. But if we begin with this recognition and face up to its revolutionary implications, philosophy can be shaped anew in a way that works in co-operation and peace with poetry. Metaphor is the way in which we appreciate meaning and connect it to bodily experience, not a dispensible ornament on a ‘literal’ base. Beliefs constructed on the assumption that they are even capable of reflecting reality become dogmatic, entrench us in inadequate attitudes, and create conflict. ‘Emotion’ is part of our basic response to the world, and is not ‘subjective’ and ripe for repression, but rather, like ‘reason’, part of our provisional account of the world, to be shaped with increasing adequacy.

Poets have been telling us about the power of metaphor and the need to face up to repressed ’emotion’, for thousands of years. Now it’s time to start listening, and to incorporate that view into a richer and more adequate kind of philosophy. I will close with a quote from Seamus Heaney (who died a year ago), which I also found in the same TLS article as the one from Yeats above:

“Within our individual selves we can reconcile two orders of knowledge which we might call the practical and the poetic…. each form of knowledge addresses the other and… the frontier between them is there for the crossing.”

Paolo Uccello 1397 – 1475. The Battle of San Romano 1432.

How does an artist represent three dimensional space and an illusion of depth on a flat surface? One early example of how this can be done would be to look at the work of Paolo Uccello who was born in Florence in 1397, his father was a barber-surgeon, his mother a high-born Florentine. Uccello is his nickname, Paul of the birds, so named because he liked to paint birds and other creatures. He was a mathematician and painter and is remembered for his development of perspective, a method of producing a sense of space and depth in a painting, there are other ways such as with the use of colour. The Egyptian and Byzantine artists had totally disregarded perspective, Giotto in Italy had made some strides to obtain this sense in his wonderful murals, now we do not find it difficult to achieve providing we learn a few basic rules. It was not until the early Renaissance era that perspective was used , these years between the 14th and early 17th. centuries were a time that heralded the end of the Middle Ages, it is thought to have began in Florence. New knowledge focused through the developing natural sciences was sought and collected by philosophers, scientists and artists, this new approach was thought to have been brought by Greek scholars who fled from Constantinople when the Ottoman Turks concquered the city, they brought their texts and knowledge with them, Greek and Roman mythology was studied once again and would be again by artists like Picasso.

Uccello was so interested in solving the problem of perspective that he would stay up at night attempting to find vanishing points, he was an idiosynchratic character who had no school of followers although he influenced artists such as Piero della Francesco, Albert Durer and Leonardo da Vinci, his tutor was Ghiberti who designed the magnificent doors of the Florence Baptistry. Uccello married in 1453.

The Battle of San Romano was depicted in three panels painted over several years with egg tempera on wood, the battle was between Florence and Sienna which lasted for eight hours, the forces of Florence were the victors – Italy was not unified then. These paintings were a secular commission, most artists then worked mainly for patrons in the church and so did Uccello, this tryptich was admired later by Lorenzo de Medici who did much to foster the Arts, the Medici family were a powerful dynasty who ruled in Florence. I have chosen the middle panel painted between 1435 and 1455, the three panels were intended to be hung high on three walls, they are now separated, one is in the National Gallery I think, another in the Louvre in Paris and the one I have chosen is held in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, each panel is about three metres long.

In this work we see a colourful pageant, a tournament rather than a real battle scene, Uccello was a mathematician with a purpose! In these paintings he exhibits his theories on perspective, he was not concerned with the feelings of the participants on the battlefield, the result is a rather wooden look to the characters, the horses could be rocking horses and the knights stuffed dummies, forms are foreshortened, we see a forest of lances and some are broken and lying on the ground as are two of the horses one with the knight still in the saddle, foot soldiers are bunched together in the middle distance, all methods used by Uccello to exhibit perspective as our eyes are led to the background, strangely there is a hunt also taking place across the fields. I like the use of the warm and rich colour, for the horse’s bridles he used gold leaf and for the armour silver leaf, which has tarnished over time. Uccello was a man of the Renaissance but as with many artists he also had knowledge the past, in this case earlier gothic art. The work is more like a fairy tale in pictures even though it depicts an historic violent event, I think that is why I like it.

Bernard Berenson, an art critic who wrote about Renaissance art in Italy was perhaps a little harsh when discussing Uccello’s work, he pointed out that art is not simply skill or a show of dexterity or to be used for scientific purposes, I would agree but Uccello did achieve what he set out to do, and as early example of perspective he was successful. Berenson worte ‘ Florentine art rushed to its end’ because of these failings, other schools of art in Italy prospered. Sadly Uccello went the same way, spending his latter years forgotten and lonely with a sick wife, he died in 1475.

Image from wikipedia,

The 2014 Summer Retreat

The Middle Way Society’s summer retreat at Anybody’s Barn, Worcestershire, finished yesterday, and I hope that in a few weeks we can put up a page containing various comments from all the Retreatants. However, for the moment I thought I would just post some of my own reflections on it.

The retreat was the first one that has been organised by the society (as the 2013 Middle Way Study Retreat, when the society was founded, was organised by me privately). As such it is a bit of a test-bed, but I expect it to be the first of many (the next will be a weekend retreat in Sussex in November). The overall purpose was to provide a basic understanding of the Middle Way as an approach, combining talk and discussion with practice and allowing the practice to give a wider context to the discussion. So the programme contained two 45 minute meditation sessions (early morning and late afternoon), a couple of hours of talk and discussion (two sessions of about an hour or a bit longer), and a more practical or creative activity in the evening that might take one or two hours. In between there were meals and lots of free time for walks, socialising, naps, reading, or reflection. We had silence up until 10am each morning to provide a focused start to the day, but there was lots of informal discussion at other times.

I’d arrived at this programme by gradually adapting the model I had initially learned in Buddhist retreats and adapting it so that the Middle Way, rather than an adherence to a tradition of what retreats ought to be like, was the working principle. Balance is vital. For retreats to work, people do need to treat them as a special space, and drop everyday distractions such as their mobiles, TV etc, but on the other hand if people are forced into too much of a ‘disciplined’ mould by an excess of one kind of activity, this is liable to produce an unhelpful reaction. I wonder very much about the long term efficacy of extreme meditation retreats, where people do 8 hours of meditation or more, as though meditation was an end in itself and more of it is necessarily better. If one wants to integrate the effects of meditation into one’s life, I think one stands a lot more chance of doing this through integrated activity: though that doesn’t mean that MWS couldn’t run retreats in the future that put a bit more relative emphasis on meditation.

One thing I think I learned from the retreat is that events that one thinks might be very disruptive are not necessarily so, as long as people maintain commitment to the retreat space. Two people had to leave less than halfway through the retreat, and another stayed locally off the premises and had to come and go a lot because of their personal circumstances. On the rather rigid model of a retreat that I had absorbed from my experience of Buddhist retreats, such things would either just not be allowed, or be regarded as disastrous if they happened. But retreats are for people, not people for retreats. Although I didn’t initially set out intending to be quite as flexible as I ended up being about these ‘disruptions’, I ended up feeling that flexibility of this kind was an important part of the way that retreats need to address conditions for real, embodied people. Ordinary people have all sorts of needs and problems that retreats need to accommodate if they are to help them, rather than excluding people because of the fixed idea that a variation of the normal conditions must be seriously disruptive.

The retreat was relatively small (7 people), and only just financially viable (many thanks to Anybody’s Barn for being flexible with their charges), but if we can attract that many people to a successful week-long retreat after only a year of existence, I’m optimistic that we will rapidly gain more credibility and begin to run an increasing number of viable retreats. The people who came along were quite varied in age, outlook, and previous experience. However, a spirit of practising the Middle Way in handling any disagreements soon came to prevail, and by the end of the week (as often happens on retreats) we had all formed bonds of friendship. If you only came on a retreat to make friends, and that was your only motive, it would still be worthwhile. It’s also impressive how easily on retreat people often get down to handling practical activities (like washing up) in a straightforward and harmonious way.

One of my own major contributions to the retreat was the talks, and one of the other points of reflection I will take away from the retreat is to keep improving the way I handled these. My tendency is to be a bit too much motivated by an overall abstract view of what I am communicating, and to go on for slightly too long, because I think about the issues in a very synthetic way, and am also thinking a bit more about the importance of the material itself than of the needs of the embodied people I am addressing. I think I improved on this compared to 2013, as I kept most of the talks down to about 30 minutes – but there were still some that went on a little too much beyond this. I also need to be more thoroughly prepared with examples and engaging stories, as sometimes I still have to be prompted to provide these.

Nevertheless, the audience did seem to get a lot out of the talks. They have all been recorded and, as with the ones on the 2013 retreat, the plan is to put them up on the website in both audio form and augmented audio (i.e. with illustrative summaries and pictures in a video format). They were differently structured from the talks I gave in 2013, and included a lot more reference to cognitive biases, drawing on the work I have been doing on these recently. Compared to last year, they were also oriented less towards addressing Buddhist assumptions and more towards just offering a straightforward and practically-oriented account of each topic (though some of the questions in discussion did still involve the relationship with Buddhism). I made a point of ending each talk with specific points about the application to practice. The headings of the talks were as follows:

- Introducing the Middle Way

- Space and attention

- Embodied meaning

- Archetypes

- Self and ego

- Theories and ‘nature’

- Responsibility

- Value

- Authority

- Groups

- Time

- Practice

Even if you weren’t there, I’d be interested to hear any comments about your responses to the format and style of this retreat – i.e. how it sounds to you. I’m also very interested to hear any suggestions for future retreats that you would like MWS to run. For myself I finish convinced that retreats are the heart and blood of MWS. The internet is all very well for spreading ideas, but it is only by meeting face-to-face and encountering each other in greater depth that we can really start to make a positive impact on changing our lives using the Middle Way.

Picture: scene from the drawing class run on the retreat by Norma Smith (photo taken by her). Although this happens to show 5 men, note that there were also 2 women on the retreat!