The other day I found a piece of the Berlin Wall: a rough shard of concrete about 3cm x 1 cm, largely grey apart from red on one side, and gift-wrapped in cellophane with a ribbon. It was given to me by a student from Berlin in 1990 (when I was teaching English as a foreign language to German students). When I re-discovered this piece, though, I began to wonder why this otherwise insignificant piece of concrete had been preserved, what it ‘meant’, and why we preserve such things. I began to realise that what I held in my hand was a sacred relic: along with the many splinters from the true cross, phials of the Virgin’s milk, bones of saints and teeth of the Buddha preserved around the world.

Those of a naturalistic (or perhaps just a Protestant) leaning tend to sneer at sacred relics on the grounds that they are fraudulent. It is most unlikely, and indeed can probably be proved by further investigation (carbon dating etc.) that most of the sacred relics in the world are not literally what they claim to be. If one thinks of religion in terms of belief that is a matter of concern, but from the standpoint of meaning prior to belief it matters little. I don’t want to defend fraudulent claims about medieval relics, but at the same time the significance of those relics to religious practitioners probably has little to do with their material origins. Instead they are objects invested with a certain symbolic significance: fetishes, idols, charms, souvenirs, mementos.

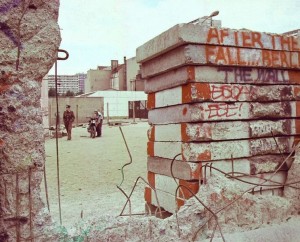

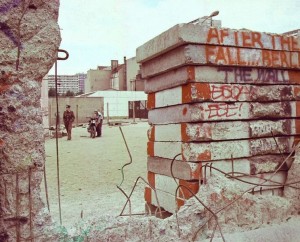

I have rather less reason to doubt that my shard of the Berlin Wall is ‘authentic’ – but if it  wasn’t, this would really have no impact on its significance. Its value as a symbolic object depends only on its connection with the destruction of the Berlin Wall. If one was looking for an event to poignantly symbolise the Middle Way and integration, the destruction of the Berlin Wall might well be it. Entrenched ideologies swept away and false divisions removed by the autonomous actions of the people – what better symbol of Migglism is there than that? It’s all the more poignant as a symbol of the Middle Way because most of the people destroying the Berlin Wall probably didn’t think of it explicitly in that way – but nevertheless they felt the joy of integration and recognised the widened horizons that occur when dogmas are removed.

wasn’t, this would really have no impact on its significance. Its value as a symbolic object depends only on its connection with the destruction of the Berlin Wall. If one was looking for an event to poignantly symbolise the Middle Way and integration, the destruction of the Berlin Wall might well be it. Entrenched ideologies swept away and false divisions removed by the autonomous actions of the people – what better symbol of Migglism is there than that? It’s all the more poignant as a symbol of the Middle Way because most of the people destroying the Berlin Wall probably didn’t think of it explicitly in that way – but nevertheless they felt the joy of integration and recognised the widened horizons that occur when dogmas are removed.

The significance of the relic, then (whether medieval or modern, ‘religious’ or ‘secular’) comes not from its physical origins but from the projections we put on it. Those projections can themselves often become stuck. I think this is what the monotheistic religions mean by ‘idolatry’ (in Islam, where it’s a very important concept, the term is shirk). If you start to think that the object, rather than just reminding you of some other significant event, concept or person, in some way gives you a shortcut to the fulfilment or integration you would get directly from them, then you are starting to fetishise or idolise the object. That means that you are giving it absolute qualities that it cannot possess. If I were to set up a Migglist shrine giving pride of place to my shard of the Berlin Wall, and expecting veneration of the shard to provide the fulfilment that the destruction of the Berlin Wall (or its equivalents in my life) actually does, then I would have turned my previous mere appreciation of the meaning of the shard into a set of obstructive metaphysical beliefs about it. This would be failing to appreciate why it does have significance to me – that is, as something that relates to my bodily experience rather than a copy of the thing-out-there.

How do we know when we have crossed that line of absolutising a mere reminder? Well, one test might well be whether we can treat the mere reminder as such – changing it or even destroying it in the full appreciation that by doing so we do not change what it symbolises. There’s a well known story about a Zen monk burning Buddha images to keep warm. If you have a shrine of objects you venerate – whether they are Buddhas, family photos, souvenirs or special books – could you happily destroy those objects? Could I take the shard of concrete that I believe to be from the Berlin Wall, throw it away and substitute another shard of concrete? Could the Catholics who venerate a splinter from the True Cross substitute another splinter from a handy nearby fence? Destroying our idols sounds to me like quite a therapeutic exercise, provided you do have a strong sense of the continuing value of what the object symbolises apart from the object.

The problem with this approach is that it can easily get confused with the long history of iconoclasm (destruction of icons) in Christianity and Islam. The original iconoclasts smashed up the icons in Byzantine churches, and the Islamic tradition followed by destroying Christian, Hindu and Buddhist ‘idols’, which they regarded as false gods interceding in our relationship to the true God. To this day you won’t see any pictures of people or animals in a mosque – only perhaps calligraphy or abstract ornamentation based on vegetation. I think the trouble with this is that in the place of fetishized objects or pictures Muslims have substituted words – the words of the Qur’an which were believed to be God’s words. Although they seem to have understood the dangers of absolutising objects or pictures, those dangers lie in the beliefs we have about them, not in the objects themselves or even their significance to us, and it is no advance to substitute other more abstract absolute beliefs for absolute beliefs about objects.

So, my suggestion is that we need to recognise that we all have sacred relics, in the sense of objects to which we attach special significance. The use of terms like ‘mantelpiece’ rather than ‘shrine’ for the places we keep these objects does not stop them being sacred or having a religious dimension. We can enjoy and celebrate that special significance – whether in art, ritual, reflection or conversation – without absolutising those objects or having metaphysical beliefs about them. If we are to stay with the meaning of those objects and enjoy them positively, a recognition and exploration of the distinction between meaning and belief seems crucial, as does a critical sense of when we might be investing our sacred relics with properties they cannot possess.

Picture: Hole in the Berlin Wall by Jurek Durczak – CCA 2.0