I was recently reading, in Amy Jeffs’ excellent book ‘Saints’, a remarkable pair of stories about the 6th century Irish Saint Scoithin (pronounced Skuh-heen).

In the first, a man is walking across a field when a ship sails by – across the field. The field remains simultaneously both water and land as the two worlds intersect, while the man has a conversation with a man called Barra on the ship. As he disappears, Barra gives the man the name of Scoithin, which means ‘flower’.

In the second story, Scoithin comes over from Ireland to visit the inspirational St David in Wales. When he is ready to go back, however, there is no ship, so St. David gives him a horse instead. The horse is miraculously able to walk on water, to carry Scoithin back across the sea to Ireland. In the middle of his journey, too, he encounters an island which turns out to be a tamed Leviathan, inhabited by St Brendan, the famous voyager. Brendan first encountered the sea monster on his journey as a threat, but later returned to make his peace with it, and to dwell on it in friendship.

I have been writing much about meaning in my books, and these stories reminded me strongly of the symbolic relationship between meaning and water. We take a ‘deep dive’ to understand something fully; we become ‘immersed’ in a subject; baptism is a symbolic immersion in new meaning, to change the direction of one’s life; the nagas of Buddhist mythology, symbols of wisdom, live deep in the sea. I expect you can find your own parallels. The properties of water lend itself very well to this recurrent metaphor. It is much more flexible than solids, but nevertheless has weight and coheres. It sustains life, but can also threaten it without the context provided by any solidity at all. If water is meaning, then earth (or solidity) is belief. We rely on earth to provide us with practical support and sustenance, but it can easily dry out and become rigid. We may assume it is permanent and final because of its solidity, but it, too, keeps changing form.

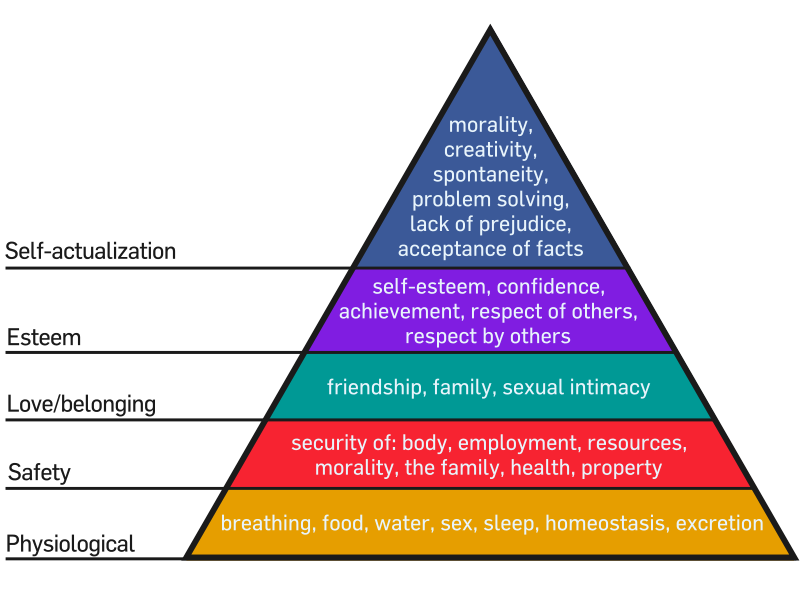

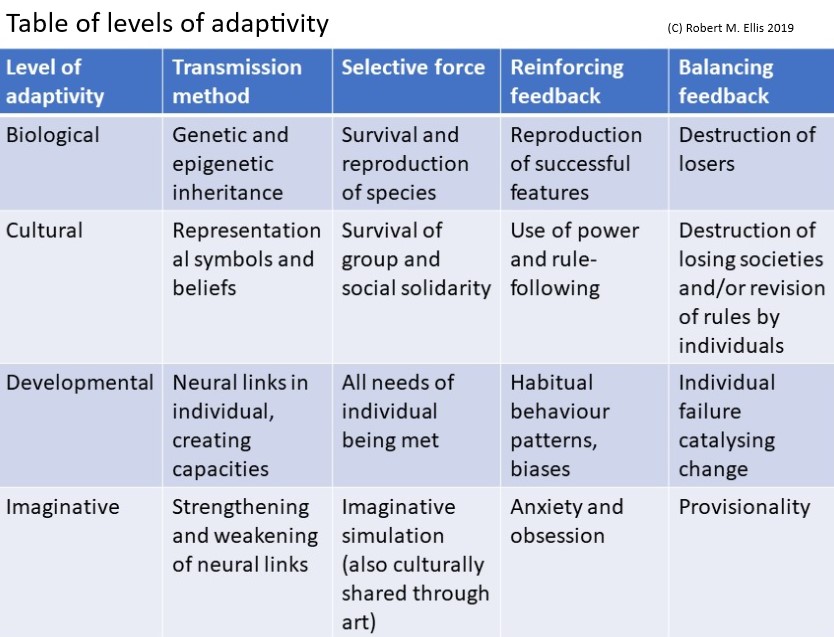

In human experience, meaning is all the potential associations that we engage with through the imagination. Words, sounds, and images are meaningful to us because we associate them with other experiences or other symbols. Neurally, meaning is a massive set of links in our brains and nervous systems. Belief is a subset of meaning, a set of associations and links that we have made (or could make) into propositions as the basis of action. However, people constantly confuse meaning and belief by assuming that belief is necessary to meaning, rather than the other way round. Much of my writing about meaning involves a protest against the entrenched representationalist tradition in our thinking, which relentlessly bases meaning on belief rather than belief on meaning. To come back to the metaphor, however, water suffuses earth and allows it to adapt and change: earth is practically dependent on water’s flexibility, but water does not always depend on earth.

Water is thus a potent symbol for the inspirational role of the imagination, allowing us to return to that underlying flexibility when we have become stuck in attitudes that are in conflict with conditions. The first story of Scoithin reminds me particularly of the way that that inspiration is always present, as long as we can maintain a connection to it. Thus although we may have very sophisticated beliefs about the world formatted by our goal-driven and representationally dominated left brain hemispheres, we also need these beliefs to be constantly connected to new possibilities through the sensual and imaginative openness of right brain hemisphere functions. As we walk across the functional, dry field, the flexible sea is always there potentially, sometimes bursting through dramatically. It’s also striking that Scoithin gains his name through a connection with this underlying meaning, not through any construction of beliefs.

In the second story, of Scoithin crossing back to Ireland on a horse, we are also reminded of the ways that meaning can provide us with new beliefs to fit a new situation. The flux of meaning can be ‘firmed up’ at any point so that we can cross into a new situation when we need to do so. This is a practical need in human life. We need the left hemisphere to formulate beliefs about the world and about our actions in it, for entirely practical purposes. The mistake we often make is to assume that the beliefs come first, that they are basic and permanent. The inspiration for this comes from Christian religious tradition in this case, as represented by St. David. It’s also striking that in his encounter with St. Brendan in the middle of his journey, Scoithin encounters an integrative application of such inspirational meaningfulness. Brendan has returned to the Leviathan, not to beat it, but to make peace and develop friendship with it. What we take to be most threatening and uncontrollable only requires new imagination to be reframed in a way that helps us to begin to address the conflict. If two parties to a conflict are dried out and stuck, they remain opposed indefinitely, but to make peace, they need the fluidity to start thinking differently.

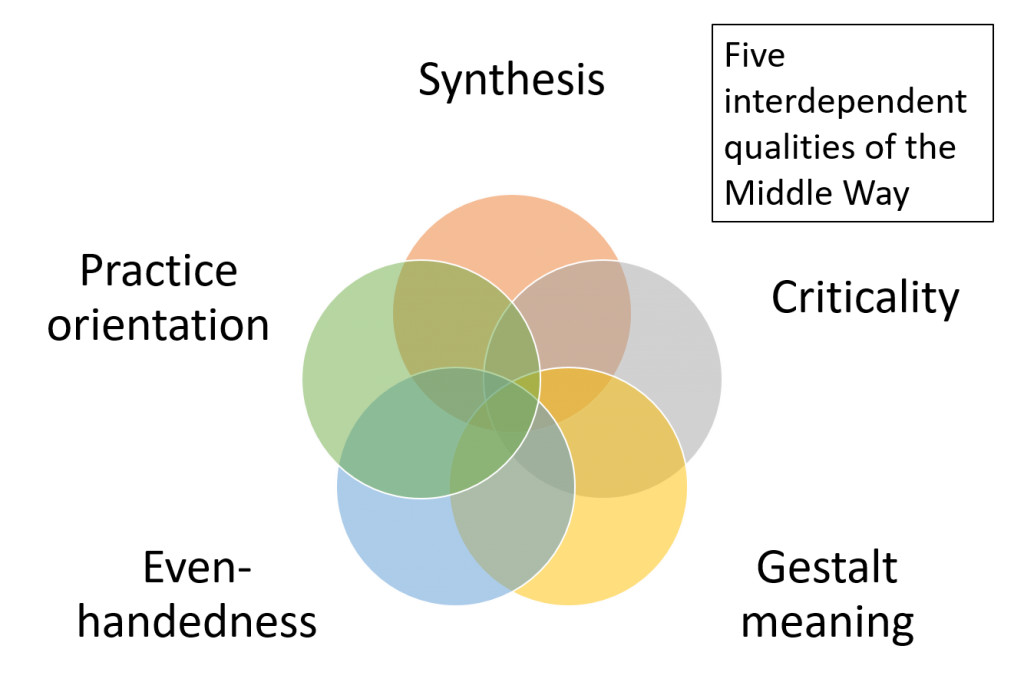

The waters of meaning are a crucial aspect of the Middle Way, with both extremes in any conflict locked in by their lack of fluidity. The Five Principles of Middle Way Philosophy all involve making a connection to the waters of meaning rather than only appealing to ‘true’ or ‘false’ beliefs – scepticism critiques solid stuck beliefs by reminding us of watery uncertainty, provisionality formulates new adequately fluid beliefs, incrementality involves thinking in degrees (as water moves), agnosticism defends the sources of the spring against those who would block it up, and integration dissolves the conflict between two solidly dried-up positions.

If we need stories to remind us of the values of the Middle Way, they can be found in the most unexpected places, because practical wisdom can be expressed in the context of any complex human tradition, even if those same traditions have got stuck in their formal expressions of belief. I draw a lot of inspiration from early Christian sources, though I can never subscribe to what are widely understood as ‘Christian beliefs’, which I think miss the point of the meaning that the Christian tradition has tapped into. The underlying symbolism of meaning as water can also be found in all sorts of other contexts.

………………………………………………………………………

My understanding of meaning is discussed in my forthcoming book (Sept 25) Embodied Meaning and Integration, and the inspirational understanding of meaning in religion was also explored in my previous book Archetypes in Religion and Beyond. Amy Jeffs’ book ‘Saints’ is linked here.