My own habit when I write even the more academic of my books is to freely use the first person: “I want to argue…”. Of course I’m still trying to put forward a case that has wider significance than just for me, but the use of the first person seems a vital aspect of honesty in argument – to show that it’s me arguing from my perspective, and I’m not pretending to be God. The I is a provisionality marker. So it sometimes comes as a shock when I realise just how much insistence on the use of the third person there is in many corners of schools, colleges and universities – particularly in the sciences, both natural and social, and for some reason also in history. Sometimes that just means lots of impersonal constructions like “it is argued that…” or “this evidence shows that…”, but when helping someone with the proof-reading of their dissertation recently I found that they referred to themselves throughout as “the researcher”. This degree of third person pretence seems very jarring to me, and the reasons I reject it have a lot to do with the Middle Way view of objectivity I want to  promote.

promote.

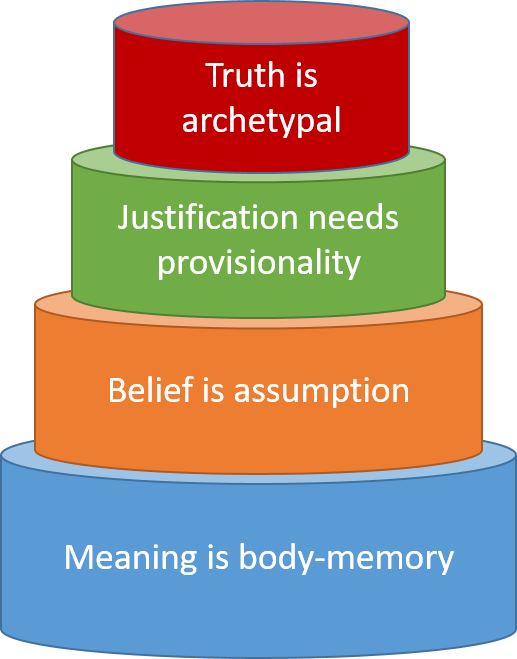

The reason that many teachers and academics drill their students to write in the third person are all to do with “objectivity”. The idea is that when you write in the third person, you leave yourself out of it. You’re no longer dealing with the “subjective” experiences of your own life, but with general facts that can be supported with evidence. Now, as an experienced teacher, I’d agree with the intention behind this – students do need to learn how to justify their beliefs with reference to evidence or other reasons, and learning to do this is one of the benefits of education. But I’m also convince that this is the wrong way of going about it. Whether or not you use the third person doesn’t make the slightest difference to whether or not you use evidence to support your claims and argue your case critically – but it does reinforce the apparently almost universal human obsession with the idea that you have ‘the facts’, or ‘the truth’ – an implicitly absolute status for your claims. If you really believe that you have ‘the facts’, then the evidence is just a convenient way of getting others to accept the same ‘facts’ that you believe in, not a source of any possible change of view. The ontological obsession hasn’t just emerged from nowhere, but is fuelled by centuries of post-enlightenment linguistic tradition.

Far better, I would argue, to use the first person to own what we say, in the sense of admitting that it’s us, these fallible flesh-and-blood creatures, who are saying it. Then the objective is objective because we have argued it as objectively as we can, not because we are implicitly pretending to view it from a God’s eye view. If we really recognise that objectivity is a matter of degree and depends on us and our judgements, then it is not enough to merely protest that we don’t really mean it when we use ‘factual’ language that habitually bears an absolute interpretation. If we are to bear in mind the limitations of our perspective in practice, we need to constantly remind ourselves of those limitations. The use of the first person offers such a reminder.

Objectivity depends not on ruling ourselves out of our thinking so as to arrive at pure ‘facts’, but rather on acknowledging our role in reaching our beliefs. Recognition of evidence of the conditions around us needs to be combined with a balancing recognition of the limitations with which we are able to interpret such evidence. Neither idealism nor realism, neither mind nor body, neither naturalism nor supernaturalism: but a recognition that none of these categories are ‘factual’ – rather they are absolutizing limitations on our thinking. If we are to take the Middle Way as the basis of objectivity, we need to stop falsely trying to rule ourselves out of the language with which we justify our beliefs.

I’ve spent enough time in schools and universities to know that academic habits are not easily reformed, and that we will probably be stuck with these third person insistences and their cultural effects for some time to come. No teacher will want to disadvantage their students in an exam by teaching them to use the first person if they know that the students will lose marks if they do so. But please let’s not use or spread this unhelpful custom needlessly, and let’s take every opportunity to challenge it. To use the first person to refer to our beliefs is to connect them to our bodies and their meanings and perspectives – which is one of the prime things we need to be doing to challenge the deluded absolutised and disembodied interpretations of the world that are still far too common.