In the aftermath of World War 2 and since, controversy has raged about Carl Jung’s attitude to Nazism, with some condemning him as a Nazi sympathiser, and others defending him in the strongest terms. After reading Deirdre Bair’s detailed biography of Jung, and following up my recent post (and as yet unpublished book) on Jung and the Middle Way, it seems increasingly clear to me that this is a classic case of a messy Middle Way strategy being misunderstood by polarised interpreters on both sides.

Jung was a citizen of Switzerland, which remained neutral throughout the Second World War. However, throughout the 1930’s he remained the president of an international psychoanalytic society that was based in, and dominated by, Germany. From the time of the rise of Hitler in 1933 this society was subject to Gleichgeschaltung, the regulations by which the Nazi government ensured conformity to Nazi values in organisations of civil society. In many ways Jung was a convenient tool for the Nazis, as they were able to use him as a source of credibility for their gleichgeschaltet version of psychoanalysis, purified of what they considered the corrupting Jewish influence of Freud with his decadent emphasis on sexuality. Although there was ambiguity in this position, because the society was formally international, the Nazis were able to manipulate that ambiguity, and he was only finally able to resign from this presidency in 1940.

It is this involvement, together with a number of incautious public statements about the psychology of races and nationalities (some of which generalised about Jewish psychology as distinct from other races) that form the basis of a case against Jung that has been raised on a number of occasions by his detractors, and even led to one (not very realistic) proposal that he be prosecuted at the Nuremberg war crime tribunals. For his critics, any compromise with Nazism or involvement in Nazi-dominated organisations makes Jung a Nazi sympathiser, and any generalisations about the psychology of Jews make him anti-Semitic.

However, Jung’s position was highly ambiguous. On his own account, his motive in remaining involved with the Nazi-dominated society was to maintain the position of psychoanalysis and to help Jewish psychoanalysts. If he had tried to take a position of purity and refused to be involved, he would have lost the possible opportunity to help psychoanalysis survive in Nazi Germany, and the opportunity to help maintain the status of persecuted Jewish psychoanalysts. After 1940, with the cohesion of the international society destroyed and Freud having fled to England, it is fairly clear that he recognised such hopes as naïve. However, he did manage one substantial achievement, which was to employ an (ironically Jewish) lawyer called Rosenbaum to introduce lots of loopholes into the anti-Semitic regulations being introduced to the society by the Matthias Goering (cousin of the more famous Goering) – who effectively developed political control over it.

As in many such highly charged and polarised political contexts, there is plenty of evidence that can be seized upon and interpreted one way, and also plenty of evidence the other way. Any case thus becomes overwhelmingly a product of confirmation bias. There is also plenty of scope for hindsight bias if we assume that the attitude Jung took to Nazism earlier in the 1930’s should have been based on their later actions – but nobody knew the full horrors to come. Highly unscientific generalisations about the psychology of races were also common currency at the time.

Later in the war, Jung also became involved in support of a plot to get Hitler overthrown, effectively providing advice about Nazi psychology to a US secret service operative working in Switzerland, as well as psychoanalytic support to a close friend who was more directly involved, both of whom were working in support of a German officer involved in a plot to overthrow Hitler. Jung’s support for anti-Nazi activities may have even gone further than this. Allen W. Dulles, the US agent mentioned, is quoted by Bair as saying “Nobody will probably ever know how much Professor Jung contributed to the Allied Cause during the war, by seeing people who were connected somehow with the other side.” Dulles went on to decline to give further detail on the grounds that most of the information was classified.

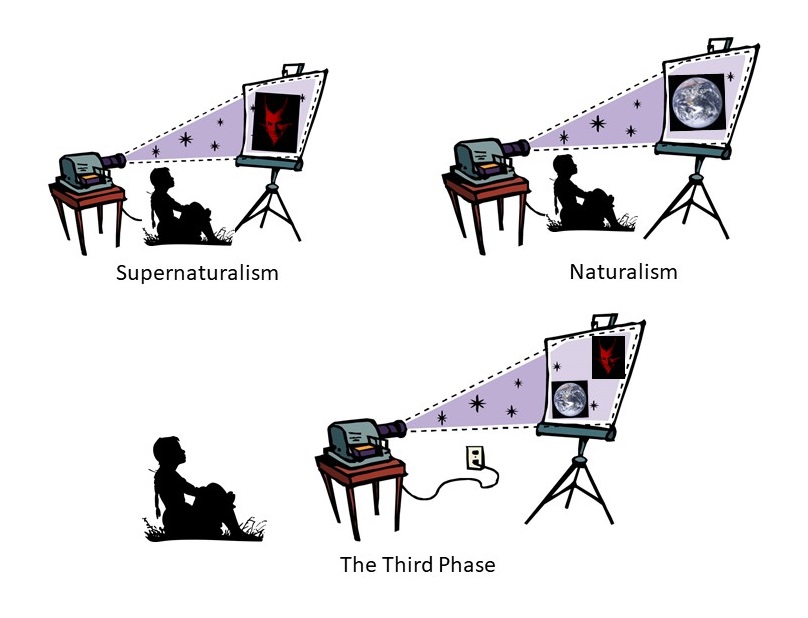

What makes me think that Jung was attempting to practise the Middle Way in any sense in this complex and ongoing situation? Partly my reading of the Red Book, which mentions the Middle Way explicitly, as I have discussed elsewhere. Partly, however, it also seems the best way of making sense of Jung’s actions. He was not ideologically motivated, though he could often be accused of political naivete. He saw the justification of one action or another in the situation, even when that situation was one dominated by Nazism, rather than solely in the terms of an ideal situation in which Nazism was not dominant. His moral values were those of individuation (as he usually called it) or what I would tend to call integration, the actual practice of which depends on the quality of judgements rather than any pre-formed general rules about the objects of those judgements.

His involvement was thus deeply messy, and he obviously left himself vulnerable to blame from both sides. It was not Nazi or Anti-Semitic, but neither was it Anti-Nazi in a way that would have made his activities less effective at the time by seeking purity from Nazism. However, it does also seem that he could have followed this path more effectively than he did: by developing more politically awareness, by seeking clearer evidence than he had before making racial generalisations, and by making the Middle Way a more explicit basis of action so as to reduce the chances of being misunderstood. Like the rest of us, however, Jung had limited knowledge, limited abilities and limited understanding with which to work, and the path of the Middle Way only requires reconciliation and adaptation to these conditions, not an unrealistic expectation of transcending them, as a basis for responsibility.

I can even find some inspiration in the way that Jung handled this difficult series of situations, not despite, but because of the many human failings that his biography has made me all too aware of. Would I, or any of us, have done better? Adopting the principle of charity seems to be the first requirement for reading the situation – a principle that allows us to appreciate the strength of messy achievement without idealising it.