‘Part of me suspects that I’m a loser, and the other part of me thinks I’m God Almighty’.

John Lennon was, with Paul McCartney, one half of the greatest song writing duo in history, and one quarter of the greatest bands in history: the Beatles (as very rare examples of absolute facts these, perhaps, represent the only time when Middle Way notions of provisionality, incrementality and agnosticism do not apply). Nevertheless, some would also have you believe that Lennon was a peace-loving, feminist icon who fought for the rights of the disenfranchised and the oppressed. A man who declared that ‘all you need is love’ and dared to Imagine a world without war, nationalism or religion. Others present him in an altogether different hue: as a violent, jealous and chauvinistic bully who abused his first wife, Cynthia and emotionally neglected his first son, Julian. On one hand we have Lennon the hero and on the other we have Lennon the villain and in many cases he is presented as either/or, with commentators unable, or unwilling to negotiate this juxtaposition. Sometimes, biographical accounts will even skim over, or ignore these conflicting characteristics entirely and instead focus solely on his musical career. I remember watching a biographical documentary which, apart from briefly referencing his peace activism (and judging it to be an immature and naive embarrassment) did exactly that.

‘When you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out… in’.

There’s a tendency to dehumanise those whom we cast as heroes or villains, creating one dimensional figures to be loved or reviled. This tendency is apparent with the treatment of exceptional individuals throughout history, such as Saints, military heroes and political activists. The recent rise of the celebrity (a term which often invites scorn, but is actually an umbrella term covering people with a wide range of skills and achievements, like Elvis Presley, Princess Diana or anyone who appears in any reality TV program) has provided  another category. There clearly seems to be a need for us to create simplified archetypes and doing so does appear to be useful, but to do this with historical people that have lived (or are still alive) can deny us a richer understanding of their, and consequently our own, humanity (and can also create real dangers, as chillingly demonstrated by the recent case of Jimmy Savile).

another category. There clearly seems to be a need for us to create simplified archetypes and doing so does appear to be useful, but to do this with historical people that have lived (or are still alive) can deny us a richer understanding of their, and consequently our own, humanity (and can also create real dangers, as chillingly demonstrated by the recent case of Jimmy Savile).

‘Well, you know that I’m a wicked guy

And I was born with a jealous mind’.

Lennon’s lyrics often seem like raw, unguarded confessions that reek of insecurity and contradiction. He seemed to be keenly aware of the conflicting aspects of his personality and didn’t shy away from exploring them in the material he released. He acknowledged both the good and the bad; the hero and the villain. While he declared that ‘all you need is love’, he also put to song the disturbing words ‘baby I’m determined and I’d rather see you dead’. Filling the space between these two extremes was a Scared, Jealous Guy who felt in serious need of Help! A perfect example of this uneasy juxtaposition can be found on the Imagine album. As well as featuring the well-known title track, which has become something of a secular hymn, it also contains the track How Do You Sleep?, a venomous attack on his former writing partner and friend, Paul McCartney, which couldn’t be any further from the sentiments expressed in Imagine.

‘Hatred and jealousy, gonna be the death of me

I guess I knew it right from the start

Sing out about love and peace

Don’t want to see the red raw meat

The green eyed goddamn straight from your heart’.

He admitted that he had been physically abusive to women – not just Cynthia – and that he had not been a very good father to Julian. He admitted that he was a bully. He also described his own experiences of childhood abandonment and later feelings of fear and insecurity, which he concealed behind a mask of buffoonery and violence. Not that this excuses the behaviour of a grown man, but it does provide us with some sense of a complex human being. Add to that his later promotion of pacifism, feminism and social justice and the asymmetrical mosaic grows greater still. In the later years of his life he became a devoted parent to his second son, Sean – with whom he seemed able to attain some sense of atonement. Unfortunately, his relationship with Julian remained strained and distant. Maybe the old wounds would have healed, had he not been shot and killed at the age of 40, but perhaps his earlier behaviour had been too damaging.

‘I really had a chip on my shoulder … and it still comes out every now and then’.

There are those that might cry ‘hypocrite’ at such apparent contradictions, but that would be over-simplistic and unfair. It’s quite possible for Lennon to have been all of these things over time (or even simultaneously), with some characteristics perhaps being the consequence of another. For instance, it’s likely that his feminism grew, in part, out of a need for redemption. That’s not to say, then, that the villain of the piece was defeated; forever to be vanquished by the upstart hero and his eye shatteringly shiny armour. No, far more likely was that the two existed side by side in an on-going (and probably uncomfortable) process of conflict and negotiation. Acknowledging someone’s flaws does not necessitate that one question the sincerity of their strengths.

‘Although I laugh and I act like a clown

Beneath this mask I am wearing a frown

My tears are falling like rain from the sky

Is it for her or myself that I cry’?

A minor deviation here, but I would like to comment on the supposed naivety and immaturity of Lennon’s political views. First of all, I feel that this is a misrepresentation of what he actually said. If we look at the two main points that critics tend to pick up on: the invitation to imagine everybody living in peace and the request to give peace a chance. Both of these notions seem far from naïve to me, in fact they seem like reasonable suggestions for incremental change. There is clearly no unrealistic demand for overnight change; just a suggestion that we consider an alternative way of conducting ourselves, with the hope that things might start to get better. In the UK similar accusations are levelled at Jeremy Corbyn, and they grate with me for the same reasons. I’m not suggesting that anyone has to agree with either Lennon or Corbyn, but the condescending disregard of their, perfectly valid, views strikes me as being unnecessary and spiteful. Secondly, the generalised criticisms of Lennon’s political views assume a fixed ideology that just doesn’t seem to have been present. He changed, altered and evolved his ideas all through his life, and was often critical of things that he had previously said or done.

A minor deviation here, but I would like to comment on the supposed naivety and immaturity of Lennon’s political views. First of all, I feel that this is a misrepresentation of what he actually said. If we look at the two main points that critics tend to pick up on: the invitation to imagine everybody living in peace and the request to give peace a chance. Both of these notions seem far from naïve to me, in fact they seem like reasonable suggestions for incremental change. There is clearly no unrealistic demand for overnight change; just a suggestion that we consider an alternative way of conducting ourselves, with the hope that things might start to get better. In the UK similar accusations are levelled at Jeremy Corbyn, and they grate with me for the same reasons. I’m not suggesting that anyone has to agree with either Lennon or Corbyn, but the condescending disregard of their, perfectly valid, views strikes me as being unnecessary and spiteful. Secondly, the generalised criticisms of Lennon’s political views assume a fixed ideology that just doesn’t seem to have been present. He changed, altered and evolved his ideas all through his life, and was often critical of things that he had previously said or done.

‘My role in society, or any artist’s or poet’s role, is to try and express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher, not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all’.

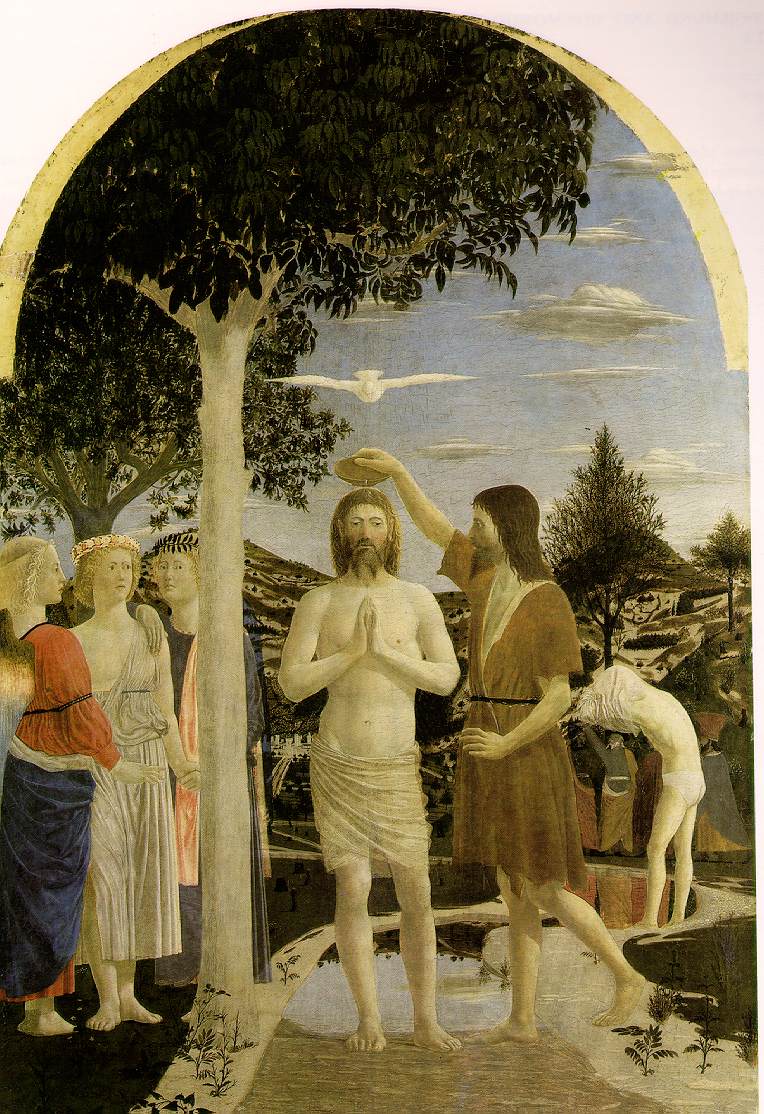

While I probably wouldn’t go so far as to put Lennon forward as a Middle Way Thinker, I do think he provides a good example of how a Middle Way approach can be useful in the consideration of those whom we admire… and those we do not. Gandhi (who has featured in Robert M Eillis’ Middle Way Thinker series) could, with some justification, be accused of misogyny and racism, but that doesn’t take away from his achievements or the legacy he left behind. The medieval Saints of Europe become figures of greater interest and inspiration when their multi-dimensional and flawed humanity can be glimpsed beneath their holy veneers (a principle that, I have recently discovered, can be applied to Jesus too). Of course, such figures need not be well known. We also create heroes and villains in our day to day lives too; looking up to, or down upon family members or colleagues, for instance. If we can recognise the messy middle from which others are composed and accept that people can be both good and bad, in different measures, at different times, then this might just enable us to become more open to those around us and more accepting of ourselves. This sounds easy on paper, but can be difficult to achieve in practice. I, for one, have a long way to go but the closer I look, the more complicated the picture becomes and the easier it gets.

While I probably wouldn’t go so far as to put Lennon forward as a Middle Way Thinker, I do think he provides a good example of how a Middle Way approach can be useful in the consideration of those whom we admire… and those we do not. Gandhi (who has featured in Robert M Eillis’ Middle Way Thinker series) could, with some justification, be accused of misogyny and racism, but that doesn’t take away from his achievements or the legacy he left behind. The medieval Saints of Europe become figures of greater interest and inspiration when their multi-dimensional and flawed humanity can be glimpsed beneath their holy veneers (a principle that, I have recently discovered, can be applied to Jesus too). Of course, such figures need not be well known. We also create heroes and villains in our day to day lives too; looking up to, or down upon family members or colleagues, for instance. If we can recognise the messy middle from which others are composed and accept that people can be both good and bad, in different measures, at different times, then this might just enable us to become more open to those around us and more accepting of ourselves. This sounds easy on paper, but can be difficult to achieve in practice. I, for one, have a long way to go but the closer I look, the more complicated the picture becomes and the easier it gets.

‘We all have Hitler in us, but we also have love and peace. So why not give peace a chance for once’?

Songs Quoted (In Order of Appearance)

All You Need Is Love (Lennon-McCartney, 1967)

Revolution (Lennon-McCartney, 1968).

Run For Your Life (Lennon-McCartney, 1965).

Scared (Lennon, 1974).

Loser (Lennon-McCartney, 1964).

Pictures (In Order of Appearance)

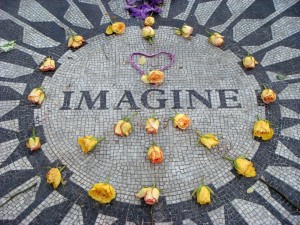

Lennon Memorial Plaque, courtesy of Pixabay.com.

John Lennon Beatles Peace Imagine, courtesy of Pixabay.com.

The Beatles & Lill-Babs 1963, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine John Lennon New York City, courtesy of Pixabay.com.