In my job teaching physics to young people from ages 11-18, I often encounter unhelpful absolutisations that act as barriers to the students being able to address conditions. For example, if a student is finding it hard to do the work that I expect them to be able to do, they may say things like “But I am no good at physics!” (absolutising the subject) or “But physics is impossible to understand!” (absolutising the object). Either way, the student who holds these kinds of beliefs has their judgement clouded by the delusions created by conceiving things in absolute terms. If instead, the student can understand the situation incrementally then they’re more likely to be able to follow the most basic imperative in Middle Way philosophy by making judgements about their learning on the basis of beliefs that are as free from delusion as possible. In this article, I explore the connection between the Middle Way practice of incrementality and the ‘mindset’ model in teaching practice.

Two mindsets

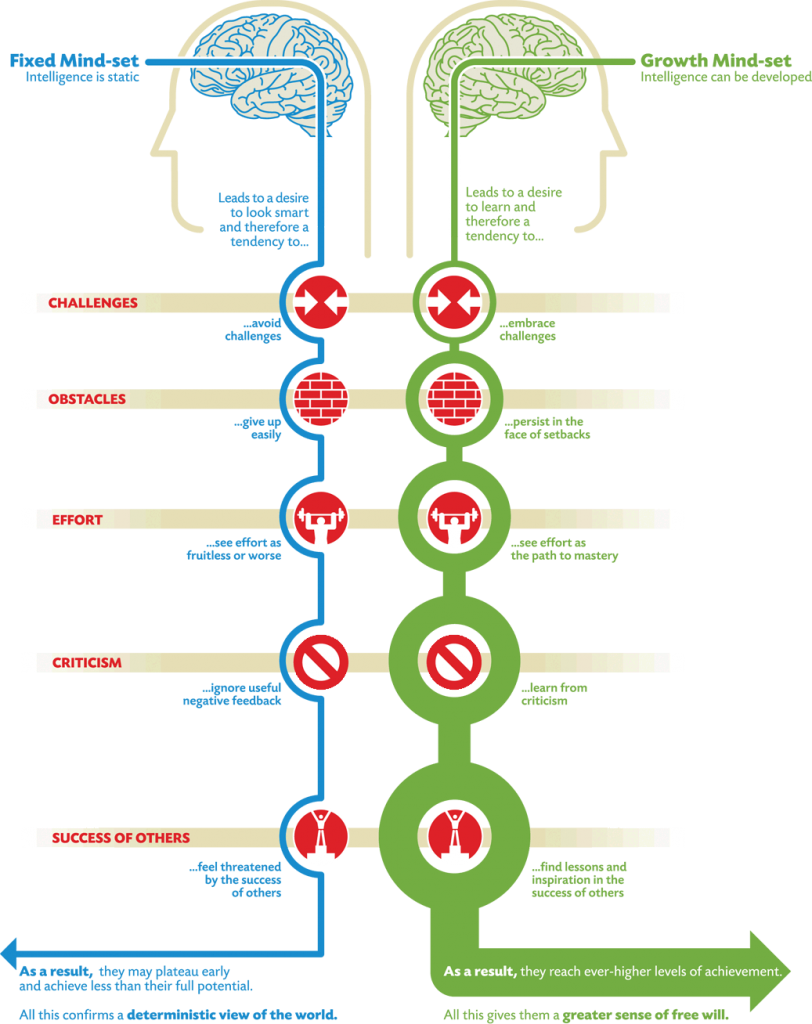

The mindset model in education was first proposed by Carol Dweck and Ellen Leggett in their 1998 paper A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. In the formulation of this model that is well known in modern educational circles, absolutising one’s self (e.g. “But I am no good at physics!”) is a judgement made by a student with a ‘fixed mindset’. The graphic by Nigel Holmes (below) sums up this belief using the phrase “Intelligence is static”. In my example, the student believes that their intelligence with regards to physics problems is static and cannot be further developed. This maintains a self-reinforcing feedback loop, where the student – in order to save face – avoids challenges, gives up easily when encountering obstacles, sees effort as fruitless and thus ignores useful criticism. They feel threatened by the success of others (whom the student regards as innately and absolutely “Good at physics”) and through a lack of engagement they fail to make the kind of progress with learning physics that they would otherwise make.

The second, more productive mindset is referred to as a ‘growth mindset’. It does not represent the opposite absolutisation (i.e. believing that “I am good at physics!” or “Physics is easy!” – which are really just another kind of fixed but positive mindset) but a middle way which recognises that intelligence can be developed, but only if the subject is willing to allow it to develop. Avoiding the fixed mindset means that a student will embrace (appropriate) challenges, persist in the face of setbacks (to a reasonable extent), and to see effort as the path to mastery. A more adequate self-correcting feedback loop is established because the student is open to learning from useful criticism, and they can find lessons and inspiration from the success of others. By experiencing progress in their study of physics they have a greater sense of being responsible for their ability to learn, avoiding the absolute of determinism.

Why do students believe in a fixed mindset?

As usual, the reasons for the entrenchment of a fixed mindset are complex. However, one really obvious factor is the attitude of influential members of earlier generations: parents, teachers, voices in the media. When some people first discover that I am employed as a physics teacher they seem to be quite happy to immediately tell me that they “were never any good at physics” or that they “dropped physics as soon as they could when they were at school”. I don’t get the impression they’re doing this to avoid feeling intimidated by the knowledge and understanding that I have that presumably they don’t. It appears acceptable to them to believe that people either ‘get’ physics or they don’t – and this sidesteps having to consider whether they were taught in a competent way, or whether they made the necessary effort to learn physics when they were being taught. It may be that they never saw the relevance of understanding physics (which, up to some age, they were compelled to study) and that they’ve never noticed any adverse effects of a lack of physics in their lives so far.

There are also the gender-related expectations communicated (wittingly, or unwittingly) to young people, which vary in their precise details but seem to be well represented in the stereotype of physics and engineering as being “boys’ subjects”. There have been studies of the factors behind gender-imbalance in the take-up of certain A-level subjects in schools in England and Wales, and I’ve been involved in a minor way with the Institute of Physics’ Improving gender balance project which is investigating the effectiveness of different strategies which aim to improve the balance in subjects with a disproportionate number of boys (or girls!). I’ve not done any formal analysis of the numbers of boys and girls who tell me that they’re “No good at physics!” or they think that “Physics is too difficult.” but I certainly hear it from both boys and girls, although perhaps slightly more often from girls.

A third thing that encourages the fixed mindset is the way that famous physicists are presented to students as ‘geniuses’, both in popular culture and perhaps unwittingly also within school education, where we should perhaps know better. Albert Einstein is the classic example. The problem with the genius model of excellence in science is that it reinforces the idea that you have to be innately special to excel at physics, and that it is only a very few people who are lucky enough to have this rare talent. Einstein once made the modest claim that “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.” This kind of remark that hints at a growth mindset gets lost in the hype and mythos surrounding Einstein the eccentric genius, the ‘one of a kind’ plaudits, which seem to be so much more palatable to the general public.

Cultivating a growth mindset in the classroom

How, then, can I encourage students to believe the growth mindset rather than the fixed mindset? One way is to model a growth mindset myself. At the time of writing, we are five weeks into the new school year and I’m still struggling to accurately remember the names of all the children that I’ve not taught in previous years. The most acute case is my science class of 11 year-olds, who are completely new to the school. I am making a point of explaining to them how I’m going about remembering their names, as it isn’t something that comes easily to me. I’m modelling the growth mindset in action by embracing the challenge with good humour (I’ve got to learn their names, so I might as well have fun doing it), I’m persisting in the face of setbacks (keeping on trying to use their names, even when I get it wrong so often), I’m showing that I’m making an effort (refusing their help until I really really need it, and then encouraging clues rather than just supplying the forgotten name) and I’m learning from their criticism (which more recently has involved them suggesting helpful mnemonics). They’ve helped in this by providing an environment in which it is safe for me to fail over and over again, and by praising my effort rather than any innate ability to remember names with ease.

Providing opportunities for failure to occur in a safe way so that students can learn that (repeated) failure is usually a necessary step towards better understanding a subject. The earlier this can be put into practice, the better – I meet a lot of students (even the older ones, who are working at quite a high level of achievement in physics) who would rather not try at all than try and encounter failure. A classic example of this is students sitting and waiting for me (or someone else) to reveal “the correct answer” to a problem that they are supposed to be trying to solve themselves. A superficial examination of the reasons for this yields answers like “Well, there’s no point me writing stuff down if it is wrong!”.

A third technique involves making careful use of the way that I speak to students about the inherent challenge in the process of learning. The most useful advice I’ve had about this is about appending the word ‘yet’ to fixed mindset phrases that students use: for example, “I don’t get this” becomes “I don’t get this yet” or “I’m not good enough to do the exam” becomes “I’m not yet good enough to do the exam”. The word ‘yet’ is not essential, of course, as can be seen from the example of how “There’s no way I can do this” can become “I can’t see a way of doing this right now.” This more or less seems to amount to skilful use of provisionality markers, as previously discussed in one of Robert’s blog posts.

A third technique involves making careful use of the way that I speak to students about the inherent challenge in the process of learning. The most useful advice I’ve had about this is about appending the word ‘yet’ to fixed mindset phrases that students use: for example, “I don’t get this” becomes “I don’t get this yet” or “I’m not good enough to do the exam” becomes “I’m not yet good enough to do the exam”. The word ‘yet’ is not essential, of course, as can be seen from the example of how “There’s no way I can do this” can become “I can’t see a way of doing this right now.” This more or less seems to amount to skilful use of provisionality markers, as previously discussed in one of Robert’s blog posts.

A fourth involves incrementalising absolutes by persistent questioning to go from the general to the specific. For example, a student who comes to a revision lesson may say “I don’t understand anything in physics!”, to which I respond “Give me an example of something you don’t understand.” and so on until you’ve gone from a blanket rejection of the whole subject to something quite specific, like not realising that a term like ‘resultant force’ just means something like the ‘overall force’, rather than being a new type of force in addition to things like friction, weight, air resistance and so on.

A final simple practice involves a general ‘no hands up’ policy during teacher-led questioning in the classroom. I’ve been amazed at the difference this simple technique makes. Previously, with children putting their hands up to indicate that they want to be picked to answer a question, those who considered themselves to be ‘no good’ at the subject could opt out by not ever putting their hand up. The division between those who considered themselves ‘no good’ and those who thought that they could answer would be reinforced in a feedback loop. A better practice is to make it clear that anyone could be called upon to respond out loud, to pose the question, to give time for all to think about it (no hands up) and then to ask a specific student to share their thoughts. It also helps to praise the effort made, to valorise trying even if it involved failure, and not to praise a student for ‘being correct’ or innately ‘clever’.

Concluding remarks

I’m not claiming here to offer anything radically new in terms of pedagogy. The examples of practice that I mentioned above seem to be the sort of thing that experienced teachers typically do to get students to see that they are capable of making progress, if only they’ll allow themselves – and the fact that they align well with the mindset theoretical framework just gives a pleasing coherence. The experience of students in the past, or in other schools currently, may have been different if teachers did, in fact, tell students that they were “no good” at this subject (or even worse “no good… just like your brother/sister/mother/father was no good at it”), or if the education system itself assumes that students have a fixed mindset and treats them accordingly by severely restricting their possibilities from very early on in their school careers.

I’m also wary of slipping into the mistake of telling children that they can “be anything they want to be, as long as they want it enough”, as that fails to address conditions adequately by absolutising responsibility. I’m told that a lot of children think that they are going to be ‘rich and famous’ because they really, really want to be rich and famous – it is easy to believe this when you see examples of celebrity culture. Maybe that attitude is not so common where I teach, but we can’t ignore the fact that some children will assume that they are ‘no good’ at certain subjects, or even the whole business of learning, because their parents before them were ‘no good’ – and it may be that there is a job waiting for them (in the family business, etc.) which doesn’t require them to have a school-level of understanding in physics! There are many other contributing factors other than the fact that a student ‘really wants’ to succeed, contrary to the popular perception, such as happening to be in the right place at the right time!

Further reading

- A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality – pdf document of the 1988 paper by Carol Dweck and Ellen Leggett.

- Fixed vs. Growth: The Two Basic Mindsets That Shape Our Lives – recommended article on the brainpickings blog by Maria Popova.

- The power of believing that you can improve – TED talk by Carol Dweck from 2014.

- Mindset – wikipedia article.

- No clarity around Growth Mindset yet – long blog piece looking at the complexity of this issue in more detail.

Picture credits

- Mindset graphic by Nigel Holmes, professional graphic designer.

- Satirical Einstein quote, own work.

- Photograph of me with magnets at a school open evening by Stephen Hill.