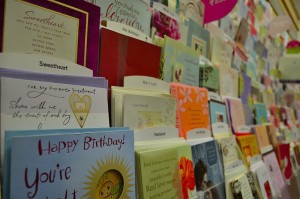

I used to have colleague who could never use a straightforward phrase about the start or beginning of anything: instead, he’d say “Your starter for ten is…”. I’m not even quite sure where this particular catch phrase comes from (I suspect some past TV quiz game). He had a great many other similar verbal mannerisms, which I would sometimes find irritating. Similar feelings assail me when I look at a rack of popular greetings cards like that pictured below. However, both then and now, I find it difficult to justify my irritation. What is, after all, wrong with cliché? Why shouldn’t people talk (and write) in whatever ways they like? Is it just a kind of cultural snobbery to decry it?

I put my own instinctive responses to cliché down largely to early literary study, as the first subject I studied at university was English Literature (before later changing courses), and one of my earliest aspirations was to be a poet. In both literary and creative writing circles (especially poetic ones) cliché is the ultimate social no-no: the basis on which unsatisfactory texts are dismissed and the prime way we tell good poems from bad ones. One of the prime values we were looking for in culture was freshness in the use of metaphor. But, looking back, nobody in those circles ever gave me a reason why this was such an important aesthetic imperative. It seemed to be simply a matter of social agreement. Sometimes I would disagree, fro example when I found that a text that might be otherwise described as ‘littered with clichés’ did also have something interesting to say. The content did seem to me more important than the form, and too much focus on the avoidance of cliché can make one focus disproportionately on the form.

But now, looking back at these issues from the standpoint of Middle Way Philosophy, I do think that there are some good reasons for generally trying to avoid cliché in one’s own writing and speech (or, to put this more positively, trying to use fresh metaphors to convey our experience). It comes down to trying not to entrench over-used synaptic tracks. If we rely over-much on one particular kind of language, this will tend on the whole to propel our thoughts down certain well-accustomed routes. Our judgements and thus our beliefs may then more easily become rigid, and ill-adapted to new circumstances. Even philosophers and scientists, who deal primarily with the assessment of beliefs, may thus benefit from some attention to the words they are using to express their beliefs. The arts, with their emphasis on developing new metaphors and new symbols, can help to constantly expand the resources we have to draw on to develop more adequate ideas about things. Our concern with such things does matter, because we are modelling our brains and their capacities as we choose one word or another.

But at the same time it also seems important not to absolutise this general rule. There may often be an asymmetry between the originality of our language and the originality of our ideas, and some people may be better at making full use of limited linguistic resources whilst others squander the immense linguistic resources on developing inconsequential ideas. The relative importance of avoiding cliché also depends very much on where you start. For some people expressing their thoughts in any kind of language, however hackneyed, may be a big step forward. What may be a cliché to us may also not be to them, because of differences in culture and experience.

The variability of what people consider to be a cliché can be judged from an interesting Wikipedia list of words that have been ‘banished’ by bodies such as the BBC and New York Times because they are considered clichéd. Some of these words seem to be in widespread general use (“conversation”), but perhaps become clichés when used in a particular way. Some are probably clichés in particular contexts unfamiliar to me, such as ‘walk it back’. There’s no mention of the ones that irritate me most, which tend to be the language of an exclusive group (obviously not one I belong to) that is unthinkingly assumed to be universal (e.g. ‘lolcats’ or ‘man flu’).

My suggestion for the general avoidance of cliché is just not to try too hard. Sometimes an original metaphor may come to you, but generally straightforward, moderately formal language does the job best. Instead of ‘Your starter for ten’, you could just boringly say ‘We’ll start with…’. Instead of ‘lol’ you could just say ‘that’s funny’. The more straightforward the language, the wider the range of people it will communicate with. An association between clichés and in-groups may thus be avoided, and any tendency you have to assume a certain limited audience for what you want to say also challenged.