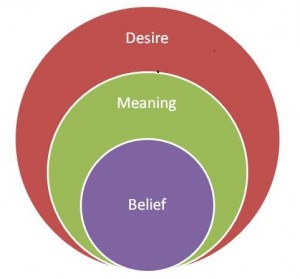

In my account of practice in Middle Way Philosophy, I have identified three (interlinked) kinds of practice area, which I call integration of desire, integration of meaning, and integration of belief. To integrate desire the central practices will be meditation, or other practices involving body awareness. To integrate meaning the central practices are likely to be the arts. To integrate belief, so far I have often focused on critical thinking as a central practice. To distinguish these types of integration and link them together in this way seems to involve a distinctive emphasis: but still, the practices of meditation and the arts themselves are widely recognised as beneficial in all sorts of ways. I have been thinking more recently of the third area as one on which I need to focus, because, although it has all kinds of links to academic practice, it is rarely either seen as integrative or linked effectively to the other types of integration. Instead, the habit of many people seems to be to fence these areas off as ‘intellectual’ concerns of interest only to a minority of boffins. The whole area of working with awareness of our beliefs and judgements, perhaps, needs a re-presentation.

I have been thinking more recently of the third area as one on which I need to focus, because, although it has all kinds of links to academic practice, it is rarely either seen as integrative or linked effectively to the other types of integration. Instead, the habit of many people seems to be to fence these areas off as ‘intellectual’ concerns of interest only to a minority of boffins. The whole area of working with awareness of our beliefs and judgements, perhaps, needs a re-presentation.

Lately I have hit on a label for the whole enterprise that might be helpful in doing this. ‘Critical thinking’ has not really been doing that job well for several reasons. People tend to associate being ‘critical’ with narrowness and negativity, which obscures the ways in which it can help one cultivate the reverse. Critical Thinking courses are also often narrowly focused on the structure of reasoning and mistakes we can make in reasoning: which are good things to study, but they miss out the whole important psychological dimension of the integration of belief. What should we call the whole study and practice of mistakes we make in thinking (not just in ‘reasoning’, but also in our emotional responses and the attention we bring to our judgements)? It has struck me recently that ‘objectivity training’ might be a better term to use for this. The term ‘objectivity’, of course, is also still used by too many philosophers and scientists to mean a God’s eye view or absolute perspective of a kind we can’t have as embodied beings, but surely if it is paired with ‘training’ it’s going to be reasonably obvious that we’re talking about helping people to make incremental progress in avoiding delusion and facing up to conditions?

So how can you train someone to be more objective? By helping them to be aware of the kinds of cognitive errors we are all inclined to make, and helping them to train attention on such errors. That’s never going to provide any guarantee that your judgement is right, but it can help us avoid certain easily identifiable sources of wrongness that we can all easily fall into through lack of attention. If you can avoid the errors, you will then have a more trained judgement, and that will give you a much better probability of making adequate responses to whatever the ‘reality’ we assume to be out there may throw at us.

There’s lots of evidence available of what those errors are, and why human beings generally tend to share them. That evidence comes from both philosophy and psychology, and one of the distinctive things I want to do is to fit the contributions of both these studies together as seamlessly as possible, with Middle way Philosophy as the stitching thread. The kinds of errors we make can be encountered in three categories:

- Cognitive biases as identified in psychology (or, to be more precise, the elements of cognitive biases that we can do something about, and that are not just unavoidable aspects of the human condition): for example, actor-observer bias or anchoring

- Fallacies, particularly informal fallacies, as identified in philosophical tradition: for example, ad hominem or ad hoc argument

- Metaphysical beliefs in dualistic pairs, as recognised and avoided in the Middle Way : for example, realism and idealism, or theism and atheism

In the end I think there is no ultimate distinction between these categories, and they often mark the same kinds of errors that have just been investigated and understood from different standpoints. What I think they have in common is absolutisation: the tendency for the representation of our left brain hemisphere to be accompanied by a belief that it has the whole picture and that no other perspectives are worth considering. We can absolutise a positive claim or a negative claim, but when we do so we repress the alternatives.

For the full argument as to how absolutisation links all these kinds of errors, you’ll have to see my book Middle Way Philosophy 4: The Integration of Belief, which makes the case in detail. However, the main reason for focusing on absolutisation is the practical value of doing so. Objectivity training is a training in bringing greater awareness to spot those absolutisations when they happen, realise they are not the whole story, and open our minds to the alternatives before we make mistakes, entrench ourselves in unnecessary conflict, and fail to solve the problems we encounter due to an inadequate engagement with their conditions.

What does objectivity training actually involve? Well, it’s something I want to focus on developing further and testing out in the next few months or years. Here are the general lines of what I envisage though:

- Becoming familiar with cognitive biases, fallacies and metaphysical beliefs – not just as isolated abstractions, but in relation to each other

- Developing understanding of why these errors are a problem for us in practice

- Becoming familiar with examples of these errors

- Identifying these cognitive errors in actual individual experience: this might involve reflection on past experience, critical reading and listening, observation of others with feedback, anticipating contexts where errors will take place, development of attention around judgement through trigger points and general use of mindfulness practice.

This is not just ‘logic’: rather it focuses on the assumptions we make. Though some of the mistakes may be identifiable as errors of reasoning, most will not, and part of the problem may well be that our narrow position seems entirely ‘rational’ to us. Nor is it just therapy, though it may have some elements in common with cognitive behavioural therapy. It needs to be an autonomous aspect of individual practice, rather like meditation and mindfulness (with which it needs to have a near-symbiotic relationship).

I think it’s really important that more people in our society learn these kinds of skills. They can be applied to our judgements everywhere: in politics, in business, in personal relationships, in spending judgements as consumers, in scientific judgement, in our attitudes to the environment, in our judgement about the arts, in leadership, in education and so on. In some of these areas, such as environmental judgement, we very urgently need to improve people’s judgement skills.

I think there is huge potential for this type of training, which is why I want to focus on developing it. But the other forms of integrative practice are also very important, which is why I hope that other people will emerge in the society who are able to take more of an effective lead in developing and teaching distinctive Middle Way approaches to meditation and the arts.