There seem to be three ways in which Christmas is meaningful to people. To Christians, Christmas is a celebration of the incarnation – of God coming to earth. To neo-pagans, Christmas is a celebration of the winter solstice. For consumerism, Christmas is an opportunity for self-indulgence, and its meaning lies in the ways that we hope to be made happy by exchanges of gifts and eating rich food. It seems to me that all three of these Christmases offer meaning in experience, but they also offer metaphysical beliefs that tend to hijack them.

The winter solstice is obviously something we all experience: or at least, those living in temperate or arctic regions of the northern hemisphere. There is a certain anxiety and foreboding about the increasing darkness, and a visceral desire for the light to return, that can make celebrating the winter solstice just a way of recognising these fears and hopes. But if it becomes part of a worship of ‘Nature’, or a desire to placate the gods of darkness, pagan beliefs are not really very far removed from theistic ones. The spring does not return because we ritualise our desire for it to do so, nor does ‘Nature’ make it return.

Consumerism, too, hits experience in some ways. We can feel, and renew, a connection with relatives by exchanging gifts with them and eating special food with them. However, an egoistic belief in ourselves and our objects of desire as unchanging can be strengthened by Christmas indulgence. Gifts can merely feed neomania, a cognitive bias that takes no account of how fast technology will change or how little gifts will matter over time. The gifts and sharing can also often just reinforce the projections in our relationships, perhaps because we haven’t resolved the archetypal view we have of parents, partners or children and recognised them fully as individuals beyond that role in our lives.

I can ride those two Christmases – they both mean something to me, but I hope not too much. A Middle Way in relation to them is relatively easy to see. However, it’s the Christian meaning of Christmas that is both more profound and more troubling. I don’t believe that God was incarnated in the form of Jesus – but I don’t deny it either. Such a claim is so obviously beyond experience that it is best left alone and not indulged one way or the other. Nevertheless, the incarnation is meaningful to me. What’s more, as someone from a culturally Christian background, I think that the profundity of its religious meaning is harder to get away from than I have often recognised. For many years I have just avoided Christmas by going away on retreat, but that has been an avoidance strategy that’s often stopped me really asking myself what it means.

How is the incarnation meaningful to me when I don’t believe in it? I find this easiest to articulate in archetypal terms (if you’re unfamiliar with archetypes, see here). If God is a forward projection of the integrated psyche, the appearance of God in human form is a reassertion of the need to integrate the symbolic God into our lives. The incarnation thus represents the unlikely, baffling glimpses of the possibility of integration that we experience from time to time, often in the symbolic form of a wise old man or woman or of a mandala-like structure.

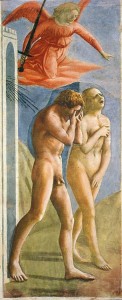

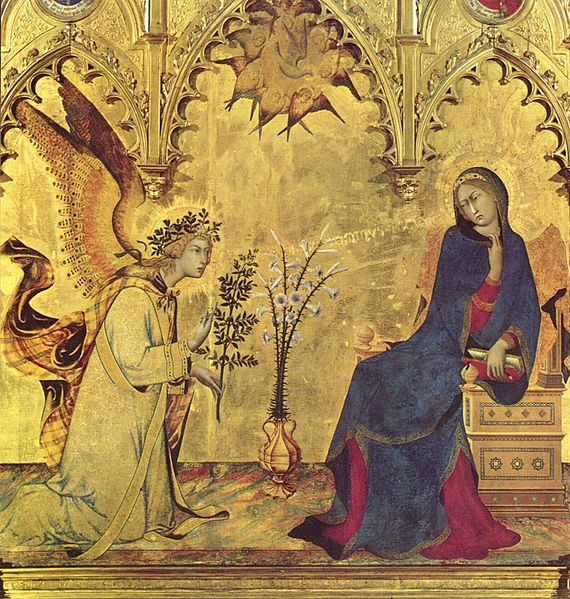

However, it’s one think to offer that explanation in theory and quite another to recognise it in experience. For me, it is the Renaissance painters who help me get to grips with this best. It seems that they really experienced that meaning fully and directly, and yet had a world-view close enough to the modern to represent it in a way we can relate to now. It is almost as though the Renaissance painters offer a moment between sleep and waking when the symbols are still vividly alive, yet we are still capable of considering them with full critical awareness. It is representations of the Annunciation that seem to capture it most often: a bewildered ordinary girl suddenly recognising a mind-boggling potential within herself. Sometimes, too, the Adoration of the Magi can offer something of that sense of awe in the face of the God archetype.

But I still fail to relate to the vast majority of what goes in churches in relation to Christmas. Not only is it still primarily about belief, but it is all still routinely objectified, trivialised, and sentimentalised. Are children in nativity plays, for example, given even the slightest glimpse of the possibility that the baby Jesus in the manger can mean something within themselves? Are the worshippers given any basic integrative practices – grounded in silence rather than endless metaphysical language – to help them cultivate the awe that they will need to recognise the meaning of Christmas? In the vast majority of churches, I think not.

So, here is my recommendation for an integrative reflection on the meaning of Christmas. Go to your nearest art gallery that has a decent collection of Renaissance art. Go when it is quiet, and preferably by yourself. Look at the Annunciations and the Nativities, and forget whatever you may have loved or hated about the story in school or church. Give yourself time to examine the pictures, and give space to allow awe to arise.

Pictures: Adoration of the Magi by Mantegna & Annunciation by Simone Martini (both public domain)