Though in many ways Jung’s Red Book is a unique text, the closest thing it reminds me of is the texts of Christian mystics who wrestled with God in their own inner experience: people like Julian of Norwich, Richard Rolle, or the anonymous author of ‘The Cloud of Unknowing’. These mystics, writing in the late Middle Ages, could not distance themselves explicitly from orthodox Christian theology in the way Jung could, but it nevertheless seems obvious to me that metaphysical beliefs really didn’t matter much to them. What really mattered was the living God they encountered within. One thing that disturbs me about the language of naturalists and so-called ‘skeptics’ is that they tend to use ‘mystic’ as a pejorative word. But if you genuinely value experience over dogma, mystics are worthy of the highest respect, and Jung is perhaps the most recent and the most striking of them: a man who tried to take scientific method and the experiential God seriously at the same time, whilst being critical of dogma, including the dogmas about God that atheists are rightly critical of. I find the same spirit of objectivity in the mystical Jung of the Red Book as I do in his psychological works.

The apparent contradiction for the mystic is that God remains supremely powerful whilst being inner. It might be assumed that those who treat God as something within one’s own mind (remaining at least practically agnostic about claims of God beyond the mind) thus reduce God to a kind of powerless abstraction, and indeed some post-modern theology can apparently end up doing this. But this misunderstanding of the implications of an inner focus confuses wider inner experience with mere intellectualisation. God does not become a mere abstraction when we treat him as an experience, because experience is recognised through the right hemisphere of the brain, and it is the over-dominant left hemisphere that creates mere abstractions unconnected to experience. Jung is very obviously not just engaged in an intellectual reduction of God to left-hemisphere terms. One of the indications of this the power of God as Jung encounters him. We’re talking about a full-blooded God here, not some sort of ‘mitigated’ God. A God who is, indeed, terrifying, in the spirit of the holy awe felt by the ancient Israelites.

Jung’s accounts of his visions bring this tension vividly to life. In the section headed ‘First Day’, Jung encounters God on a mountain path. He is terrified, but oddly enough the God himself also seems to be terrified.

As I approach the top, a mighty booming resounds from the other side of the mountain like ore being pounded. The sound gradually swells, and echoes thunderously in the mountain. As I reach the pass, I see an enormous man approach from the other side.

Two bull horns rise from his great head, and a rattling suit of armour covers his chest. His black beard is ruffled and decked with exquisite stones. The giant is carrying a sparkling double axe in his hand, like those used to strike bulls. Before I can recover from my amazed fright, the giant is standing before me. I look at his face: it is faint and pale and deeply wrinkled. HIs almond-shaped eyes look at me astonished. Horror takes hold of me: this is Izdubar, the mighty bull-man. He stands and looks at me: his face speaks of consuming inner fear, and his hands and knees tremble. Izdubar, the powerful bull trembling? Is he frightened? (p.277-8)

Jung then has a conversation with Izdubar, in which he tells him he comes from ‘the West’, with its science and rationality. On learning this, Izdubar is dismayed. He flings away his useless weapon and falls ill. This seems to reflect the initial impact of the modern outlook on God, which at first looks likely to kill him: the function of God undermined in the human psyche by the left-brain dominant explanation of the ‘natural’ world.

In ‘Second Day’ Jung finds himself on a mountain ridge with a sick Izdubar, whom he realises he loves and wants to save. But Izdubar cannot move, and is too heavy to be carried to safety. Then Jung has an idea.

I: My prince, Powerful One, listen: a thought came to me that might save us. I think that you are not at all real, only a fantasy.

Izdubar: I am terrified by this thought. It is murderous. Do you mean to declare me unreal – now that you have lamed me so pitifully?

I: Perhaps I have not made myself clear enough, and have spoken too much in the language of Western lands. I do not mean to say that you are not real at all, of course, but only as real as a fantasy. If you could accept this, much could be gained. (p.293)

Eventually he persuades Izdubar to accept that he is only as real as a fantasy “if it helps”, and Jung is then able to pick up Izdubar, who becomes “lighter than air” and carry him home. This is an extraordinary recognition, not just that God remains valuable when recognised as a human construction, but of the incrementality of the ‘reality’ involved: it is not just a question of being real or unreal, but rather of having more or less of the qualities we associate with ‘reality’, such as tangibility, extension in space, causal effectiveness, and so on.

When he gets home, despite being light, Izdubar will not fit through the door. So Jung squashes him into the size of an egg (p.295). Yet, despite being squashed into the size of an egg, God has lost none of his meaning and importance. Jung sings moving ‘Incantations’ over the egg containing God.

Oh

light of the middle way

enclosed in the egg

embryonic,

full of ardour, oppressed…. (p.300)

Come to us, we who are willing from our own will.

Come to us, we who understand you from our own spirit.

Come to us, we who will warm you at our own fire.

Come to us, we who will heal you with our own art.

Come to us, we who will produce you out of our own body.

Come, child, to father and mother. (p.303)

Jung conveys a wonderfully integrated experience here, at one and the same time recognising that we create God, that God is not something threatening us from without, and that God is nevertheless a matter of overwhelming yearning. But nevertheless, such an encapsulated God, without power, cannot fulfil all the functions of God, and Jung wishes to restore him to his former splendour. In ‘The Opening of the Egg’, Izdubar bursts out of the egg.

I: “Oh Izdubar! Divine One! How wonderful! You are healed!”

“Healed? Was I ever sick? Who speaks of sickness? I was sun, completely sun. I am the sun”.

An inexpressible light breaks from his body, a light that my eyes cannot grasp. I must cover my face and cast my gaze to the ground.

I: “You are the sun, the eternal light – most powerful one, forgive me for carrying you.” (p.307-8)

This to me conveys a powerful message about God as meaning. A meaningful God is not an inch less impressive and powerful than a real God. He remains perfect, omnipotent, omniscient and eternal in meaning. But such a God and his infinite qualities should not be an object of belief – for that would fix the nature and qualities of God in relation to everything else. Since God has the archetypal function of projecting forward a complete integration of the psyche, the form taken can vary with each person or each group sharing ideas about that supreme meaningfulness, it being only his function that creates universal consistency.

Elsewhere, Jung describes God as the supreme meaning.

But the supreme meaning is the path, the way and the bridge to what is to come. That is the God yet to come. It is not the coming God himself, but his image which appears in the supreme meaning. God is an image, and those who worship him must worship him in the image of the supreme meaning. (p.120)

This meaningfulness becomes all the more intelligible if we interpret it in the light of embodied meaning. The meaning of God does not have to be tied to beliefs about the circumstances in which propositions about him would be true, as analytic philosophers would have it. It is this representationalist assumption that makes most philosophy of religion a waste of time. Instead, the meaning of God, like the meanings of all other words and symbols, consists in synaptic links formed by associations with our active experience, and built up through inter-related metaphors that connect different areas of that experience. God does indeed reside in our bodies, but no one metaphor is solely adequate to describe him: rather it would require the synthesis of all metaphors into the widest possible meaningful experience. To ‘worship’ God should surely be to try to connect with that supreme meaning – not to reify it, but to get as far as we can in experiencing it.

Personally I find this portrayal of God in the Red Book both liberating and inspiring. One thing I have in common with Jung is a Christian background, indeed being like him the son of a pastor. In earlier life I have tried to evade God and think of him as irrelevant, but, as Jung writes:

God is unavoidable. The more you flee from the God, the more surely you fall into his hand. (p.164)

God is unavoidable, not just for those of us who have an image of God etched into our childhood experience, but even in a sense for others, since the God archetype is a dimension of human experience that may manifest in other ways using other labels, but nevertheless have the same function.

Reading the Red Book has reminded me of how important that function is to me, but it leaves me nevertheless in a continuing indecision about my practical relationship to Christianity that becomes, if anything, more loaded than it was before. Churches are rich sources of archetypal experience, but overwhelmingly still filled with people who externalise and absolutise that experience. Sometimes I encounter the wish to worship God, but any such worship seems destined to be solitary. Perhaps one day there will be a Jungian church led by people who explicitly acknowledge the archetypal nature of God at every turn: but until that day, it is only churches empty of people that I, perversely, find attractive, and where it seems possible to explore Jungian interpretations of what one encounters in solitude.

Link to the first blog in this series: The Jungian Middle Way

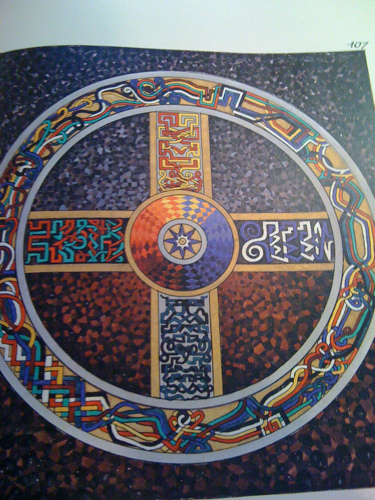

Picture: Mandala from Jung’s Red Book: Joanna Penn CCA2.0