The range of impressive developments in psychology and neuroscience in the last few decades is astonishing, and I’m personally excited to keep discovering new ones. It is a challenge to keep an overview of them, to see how they relate to each other, how they relate to various philosophical and religious assumptions, how they relate to morality, and how they relate to practice.

The more specialised work goes on and the more academic specialists artificially limit their horizons to make progress in one area, the harder it becomes for other people to keep up with them, to synthesise and to digest the implications. But we need to try – for the results are often potentially revolutionary, amounting to a third phase of scientific development (as I have put it before) – a phase where, for the first time, uncertainty is really taken into account. So that’s what I’ve made it my business to try and do, and where I think the Middle Way as a co-ordinating model can be valuable.

Let me list some of the potentially helpful psychological/ neuroscientific models that have excited me in recent years:

- The recognition of the brain as a network of connecting neurones of incredible complexity (trillions of connections) and astonishing plasticity throughout life, related to network theory.

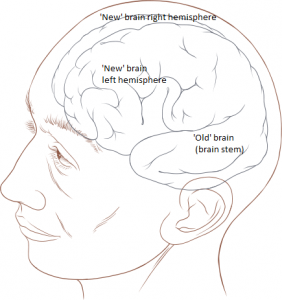

- The cyclic process of reinforcement between cognitive models in the frontal cortex (‘new’ brain) and a process of desire or anxiety in the ‘old’ brain, leading to the entrenchment of unhelpful emotional habits – unless we can use our ‘soothing system’ to soften them. (e.g. see Paul Gilbert and Marc Lewis)

- Brain lateralisation: the specialised role of the left hemisphere in maintaining goals and representations, while the right hemisphere is open to new stimuli and can relate different representational models (Iain McGilchrist)

- Cognitive bias theory: the recognition of a whole range of particular ways that our judgements about the world can be blocked and made inadequate by faulty assumptions (Daniel Kahneman and many others)

- Ellen Langer’s ‘Mindfulness’: the way that making active distinctions can both energise our judgements and make them more adequate

- Embodied meaning: The philosophical development of an account of meaning based on the neural networks created by our bodily interaction with our environment throughout life, based on psychological and linguistic evidence (George Lakoff and Mark Johnson)

- The integration of reason and emotion: recent studies have found strong neurological grounds for doubting the traditional distinction (e.g. Storbeck & Clore 2008)

- Repression: An older model found in psychoanalysis, recognising plurality in ourselves and the potential for failing to recognise unconscious and rejected beliefs, even whilst these still have an unconscious effect on us and tend to re-emerge. The potential for integration is also recognised here when repression is overcome. (initially Freud, but also Jung and later Jungians)

- Archetype theory: the recognition of common patterns of symbolisation in individual experience of both repression and integration (Jung)

So how can all these fit together? I’ll try to be as brief as I can. For the sake of brevity I’ll refer to the psychological insights listed above by their numbers.

Let’s start with the Middle Way. The basic principle of the Middle Way is that our judgements are improved by avoiding absolute or metaphysical claims, whether these are positive or negative in form. That leaves us in a realm of uncertainty, provisionality, and incrementality, a messiness in the middle in which we stand a much better chance of developing more adequate beliefs and values.

Central to engaging with that messiness in the middle is the positive recognition that we are bodies, that our operation depends on brain connections (1), and that the whole meaning of the language we use depends on our bodies (6). Making this recognition is not in any way reductionist or materialist. On the contrary, it allows us to relate our theoretical models to our wider embodied experience, rather than allowing an over-dominant left hemisphere perspective (3) to maintain false certainties. The Middle Way is about understanding and changing the way we think, not finding a new total explanation.

All these psychological developments can be focused on the key point of recognising uncertainty and following through its implications. Our responses to uncertainty, and fruitless attempts to grasp certainty, are just as much emotional processes as rational ones (7). Our habitual beliefs are closely tied to our emotional needs and histories (2), and the extent of their entrenchment needs to be recognised, but there is always hope – they can also be changed (1).

The rigidification of our beliefs makes us less flexible in changing circumstances, that rigidity being associated with over-dominant left hemisphere goals and models (3). Our over-certainty makes us liable to all sorts of identifiable specific kinds of error (4), and can also make us ‘mindless’: acting automatically, alienated and demotivated (5). We remain unaware of the ways we do this (8), and the absolutised beliefs that maintain that repression can be socially maintained through unintegrated use of archetypes projected onto people, abstractions or supernatural entities (9).

But there is hope. Addicts and neurotics can and do recover, and meditation and associated practices allow us to use our soothing systems (2). We all have right hemispheres which are capable of taking a pivotal role in integrating the potentially discontinuous and absolutised beliefs of the over-dominant left hemisphere, allowing the left hemisphere to play its equally vital role with more open and balanced beliefs (3). Some aspects of cognitive biases are just part of the condition of being human, but there are also many aspects that can be worked with and improved on (4) – all the more effectively when they are not just seen as ‘irrationality’ but in a wider context. We can develop mindfulness both in Langer’s sense (5) and the more common sense through practice. Different kinds of integration can support and stimulate each other, and archetypes do not necessarily have to be used repressively (9): they can be separated from metaphysical beliefs and positively cultivated to support the integration of meaning.

You don’t necessarily have to have engaged with all these different psychological models to recognise this overall process, but each one helps to contribute to the gathering evidence. It really helps to have sampled one or two, though, and Ellen Langer and Iain McGilchrist are probably the two most impressive individual figures I’ve come across, whose work is both accessible and fascinating. Whatever psychological model you use, remember it’s not going to tell you the whole story, but it can contribute enormously. Psychology at the moment seems to me to be the leading discipline, some way ahead of any other in terms of engaging with the Middle Way, but traditional psychological assumptions can also get in the way (for example, the belief in value-neutrality in science). In the end, psychologists also need philosophers, artists, practitioners and others to provide a wider context. But nevertheless their work is providing the most exciting pointers towards the Middle Way in today’s world.