The misconception: You make rational decisions based on the future value of objects, investments, and experiences.

The truth: Your decisions are tainted by the emotional investments you accumulate, and the more you invest in something, the harder it becomes to abandon it.–David McRaney

You Can Beat Your Brain

About an hour ago someone I’d never met before knocked at my front door. I gave him a pair of headphones, he said thank you, and the transaction was done. I don’t imagine that we’ll ever meet again.

About an hour ago someone I’d never met before knocked at my front door. I gave him a pair of headphones, he said thank you, and the transaction was done. I don’t imagine that we’ll ever meet again.

We both benefited, me and the stranger: he gained a working pair of good quality hi-fi headphones, and I was rid of an object that I really didn’t need to own. This wasn’t as random an act as I’ve made it sound, and I haven’t started giving away everything I own in a fit of asceticism or altruism… it’s just that there are some possessions that I really don’t need to hang on to, and freecycle.org exists in order to rehome those things that I don’t have the energy or inclination to sell.

A familiar story?

Here’s the backstory: a long time ago—probably over ten years ago—I bought a pair of headphones. At the time I was spending a lot of time listening to music through some tiny in-the-ear earphones, and it seemed sensible to treat myself for my birthday or whatever to a reasonably good-quality pair of hi-fi headphones. So I did. The sound quality was great, but however I adjusted them they were never really very comfortable to wear and after a few weeks of trying I pretty much gave up using them.

Every now and then I’d rediscover these headphones, wherever I’d stashed them, and try them again and then realise why I’d stopped using them. It got to the point where I’d accidentally find them, glare at them because they reminded of how I’d invested a reasonable amount of money by purchasing them, then ignore them. One more thing that I owned, but never used any more. One more thing that I might as well not own, but could not get rid of because (once again) I’d been taken in by the so-called ‘sunk costs’ fallacy.

Actually, about six months ago I re-discovered these headphones, found that the material on the ear pads had perished, and bought some replacement ear pads over the internet. Thus investing even more money in this thing that I owned, but never used. I thought I was being rational, after all – what good were the headphones if the pads were falling to bits? Buying new pads would make the headphones great again! But that was the fallacy at work. A more objective view would have been that I was ‘throwing good money after bad’, expressed very clearly as ‘the truth’ in the quote from David McRaney’s book at the top of this article.

Actually, about six months ago I re-discovered these headphones, found that the material on the ear pads had perished, and bought some replacement ear pads over the internet. Thus investing even more money in this thing that I owned, but never used. I thought I was being rational, after all – what good were the headphones if the pads were falling to bits? Buying new pads would make the headphones great again! But that was the fallacy at work. A more objective view would have been that I was ‘throwing good money after bad’, expressed very clearly as ‘the truth’ in the quote from David McRaney’s book at the top of this article.

Anyway, conditions have changed and I think I’ve now made a better decision by freecycling the headphones rather than putting them back in a box under my bed to be ignored for another six months. There’s always going to be the nagging concern in the back of my mind that I might just need those at some future point, and I’ll regret having got rid of them. But I’ve felt that often enough before, and I seem to have survived.

The ‘sunk costs’ fallacy

The headphones story is just one aspect of a greater springtime sort-out that I’ve been engaged in over the Easter holiday. And turning up unused item after unused item I’ve been realising that I’ve been reluctant to let go mainly due to the sunk costs fallacy. This fallacy is behind a huge range of dysfunctional human behaviour, from the relatively harmless (eating a whole bag of crisps, even though you’re not very hungry, because you paid for a whole bag of crisps) to the very harmful (a head of state starting a war against another nation, even though the war will not improve things under current conditions, because you had previously committed your country to that course of action based on the conditions back then).

In economics a ‘sunk cost’ is a cost that has been put into a project, and that cannot be recovered. In psychology the same term, by analogy, applies to emotional investments that have already been made: things that we cannot forget or un-do. The fallacy part comes in when we assume that we’re operating rationally (by not allowing the sunk costs to disproportionately influence our decision making) while actually operating irrationally (because of the strong emotional investment we have already made).

In economics a ‘sunk cost’ is a cost that has been put into a project, and that cannot be recovered. In psychology the same term, by analogy, applies to emotional investments that have already been made: things that we cannot forget or un-do. The fallacy part comes in when we assume that we’re operating rationally (by not allowing the sunk costs to disproportionately influence our decision making) while actually operating irrationally (because of the strong emotional investment we have already made).

Apparently this fallacy is a consequence of the way that human minds work; the prospect of losses is a more powerful motivator on our behaviour than the promise of gains—which is also known as ‘loss aversion’—which means that we tend not to treat losses and gains in an even-handed way. In David McRaney’s highly readable book about cognitive biases and logical fallacies, ‘You can beat your brain‘ (US title: ‘You are now less dumb‘), he explains the enormous success of the Farmville game on social media in terms of the sunk costs fallacy. You can read this chapter of the book on McRaney’s own website (link).

Love people. Use things.

Before I finish I’ll tell you about one more example from my springtime sort-out, one where the monetary value wasn’t a factor. And I’m not talking about the box of sixty leather bookmarks, although that was snapped up the same day by an enthusiastic freecycler whose mother apparently ‘loves all things books!’

Before I finish I’ll tell you about one more example from my springtime sort-out, one where the monetary value wasn’t a factor. And I’m not talking about the box of sixty leather bookmarks, although that was snapped up the same day by an enthusiastic freecycler whose mother apparently ‘loves all things books!’

For the past 25 years I’ve been hanging on to an A5-sized spiral-bound drawing pad, full of black pen landscape drawings that I’d done when I was about 15 years old. It was so long ago that I can’t quite remember what it was that made me start filling this book – I liked drawing and wanted to get better at it, I had time to spare during the school holidays. Anyway, the thing is that I’ve been hanging on to this pad for a quarter of a century: whenever I moved house, and that’s fairly often, the pad moved with me. I couldn’t get rid of this thing that was the only tangible reminder of the hundreds of hours I’d spent drawing these pictures in my mid-teens.

Looking through the pad of drawings a few days ago, with slightly more objective eyes, I realised that 90% of the drawings weren’t even original! I’d been working through a tutorial-style book called something like ‘How to draw landscapes‘. So I’ve removed the three pictures from the back of the pad that were my own creations, and recycled the rest. In fact I’ve gone one better and I’ve scanned these three pictures and they now live in ‘the cloud’ instead of my sock drawer.

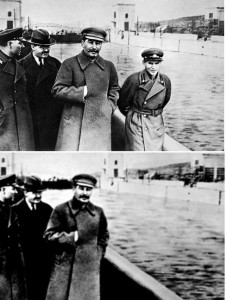

And it’s not even the pictures that have value for me, it is the meaning they hold for me and others, and this meaning doesn’t depend on the continued physical existence of the object. For example, one of the drawings was of the row of cottages where my grandparents lived for most of their lives (shown in the picture here). I know that my grandfather, in his 90s now, will find this fascinating, it’ll be something we can talk about. We can laugh together about the sheds where he accumulated about five duplicates of every kind of gardening tool – that was quite an effort when he eventually moved out and down-sized, to help him let go of 60 years worth of well-hoarded stuff.

And it’s not even the pictures that have value for me, it is the meaning they hold for me and others, and this meaning doesn’t depend on the continued physical existence of the object. For example, one of the drawings was of the row of cottages where my grandparents lived for most of their lives (shown in the picture here). I know that my grandfather, in his 90s now, will find this fascinating, it’ll be something we can talk about. We can laugh together about the sheds where he accumulated about five duplicates of every kind of gardening tool – that was quite an effort when he eventually moved out and down-sized, to help him let go of 60 years worth of well-hoarded stuff.

Let it go, let it go…

To conclude then, I’m not going to tell you that you might as well get rid of that material clutter in your life – you probably already know that! I’m not about to give you any advice about how to let go of the stuff that you’re needlessly hoarding either, there are enough minimalism blogs and progs which can help you with that. My point is this: remember the sunk costs fallacy, which lies behind your irrational reluctance to get rid of stuff that is of no value to you. And in remembering it, you’re no longer beholden to its underhand influence. If you can remember this with the more trivial issues of day-to-day living, there’s hope that you might also avoid the unethical actions that we are driven towards by loss aversion.

Looking to the near future, it will soon enough be time for the great summer sort-out, which means tackling the dreaded shed. Wish me luck.