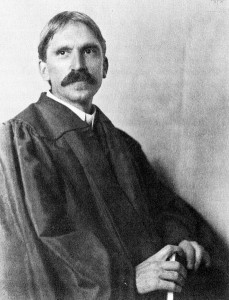

I find John Dewey one of the most interesting and inspiring figures in modern philosophical history. He was a pragmatist, meaning that he sought to prioritise practical experience over dogma as a guide to our beliefs. He was a highly synthetic thinker, particularly bringing together science and empiricist philosophy with the Continental Hegelian philosophy that had influenced him in his youth. Although he had a successful university career as a philosopher, he was far from limited to that field, and also engaged deeply in issues of psychology, education, society and politics. Above all, over a very long life (1859-1952), Dewey gathered enormous respect from many sides as a humane, liberal figure, a personal inspiration for many that was probably due to a high level of personal integration.

Dewey came from Burlington, Vermont and his cultural background is very much that of New England liberalism. He studied at the University of Vermont and then (after an interval of school-teaching) did a Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins, followed by academic posts at the universities of Michigan, Chicago and Columbia. By the time he died, at the age of 92, he left behind a massive corpus of writings, so great and wide that it is very difficult to know where to start. In those days it was not so difficult for a philosopher to also be respected as a psychologist and educationalist, and to also become a public intellectual. Not surprisingly, he stressed the value of a philosophy informed by psychology, recognising the emotive basis of cognition and thus the unhelpfulness of a purely analytic approach. Influenced by his integrative psychology and liberal politics, he stressed an approach to education that stressed the development of autonomous judgement and integrated character.

That Dewey was a Middle Way thinker in many respects comes across from a number of key writings. I am very far from having read even a substantial fraction of Dewey’s vast output, but in what I have read, the following passage particularly stands out in encapsulating Dewey’s stance as a Middle Way thinker. It was written in his old age, in 1944 when he was 84 years old:

“[My view] assumes continuity; [whereas the dominant theories of knowledge] state or imply certain basic divisions, separations, or antitheses, technically called dualisms. The origin of these divisions we have found in the hard and fast walls that mark off social groups and classes within a group: like those between rich and poor, men and women, noble and baseborn, ruler and ruled. These barriers mean absence of fluent and free intercourse. This absence is equivalent to the setting up of different types of life-experience, each with an isolated subject-matter, aim, and standard of values. Every such social condition must be formulated in a dualistic philosophy, if philosophy is to be a sincere account of experience. When it gets beyond dualism – as many philosophies do in form – it can only be by appeal to something higher than anything found in experience, by a flight to some transcendental realm. And in denying duality in name such theories restore it in fact, for they end in a division between things of this world as mere appearances and an inaccessible essence of reality.” (Democracy and Education)

This passage brings out Dewey’s concerns about social division, and his recognition of the relationship between group identity and dogma, in which one group will seek absolute allegiance and reject a counter-group by using metaphysical beliefs as rallying point. It also shows his ability to see through the religious absolutisations that were still highly influential in his lifetime. It will not be sufficient to break down class divisions in society, he is telling us, merely to appeal to a classless God or a classless political ideal – we will need to recognise that this appeal itself will create a new dualising effect, an absolutisation in which the ‘other’ is rejected. The only solution to such a re-emergence of conflict, even in the beliefs of those who may sincerely want to overcome it, is continuity – to see how even opposing beliefs and ways of life may nevertheless be judged using the same incremental scales in relation to similar conditions. In this continuity lies the possibility of overcoming conflict. This dialectical aspect of Dewey’s philosophy is influenced by Hegel, but he left behind all the more dogmatic elements of Hegelianism.

Linked to this viewpoint is Dewey’s well-known emphasis on democracy. Dewey might fairly be accused of idealising democracy, but very often ‘democracy’ comes to mean for him something like the Middle Way – not just a system of government but a whole way of determining the values of society that respected autonomous development and the hard-won fruits of experience. At the same time democracy needs to reject raw power and its appeals to dogma to maintain itself. The values of democracy require those of education – of the development of autonomous individuals able to make adequate judgements for themselves and reject the dogmas used by tyrants. This kind of approach seems to reflect some of the best elements of the American tradition of liberal democracy.

Dewey’s approach to ethics was consistent with his belief in the importance of autonomous judgement in the public realm, and with continuous thinking rather than appeals to absolute in individuals. He rejected that fact-value distinction, and stressed the development of a reflective equilibrium, taking into account as many factors as possible, in the development of an adequate ethical standpoint. This subtle psychological ethics has more recently been adopted by such figures as Mark Johnson and Philip Kitcher (interviewed in the MWS podcast), and offers the promise of a far more adequate ethics than a mere appeal to one dominant rational ethical theory to solve all our problems (such as utilitarianism or Kantianism).

Of course, there are some ways that I think Dewey fails to hit the Middle Way on the evidence so far. However, I am uncertain how far some of these judgements are fair because of the size and breadth of his writings and the limitations of my reading so far. Perhaps the major limitation is that Dewey identifies himself (and is often identified) as a naturalist. Naturalism can take all sorts of subtle forms, and does not necessarily mean crass materialism or what Mark Johnson calls ‘science-mongering’, but it nevertheless to me seems mistaken because to be worthy of the name it must still in some respect be seeking an account of right understanding and values in accounts of ‘nature’ rather than in the balancing of our own approach to what we experience. Dewey does at times seem to appeal to nature and to evolution in ways that I sometimes remain doubtful about, even though those doubts really need further investigation.

Dewey’s possible strayings from the Middle Way, if they exist, remain controversial and subtle, and may often be the result of limitations of information available to him in his time as opposed to ours (for example, he would have known little about meditation). Such issues are utterly dwarfed by Dewey’s positive achievements as a subtle, integrative, humane and compassionate figure, active in society as he was in the intellectual realm. Nevertheless, he remains neglected by modern analytic philosophers, psychologists and politicians alike, who often seem unable even to really take in, let alone emulate, such a synthetic figure from an earlier age.