I’ve been asked from time to time about psychic energy, which is an underlying concept that can be used to help understand repression, and thus helps to explain how absolutizing beliefs can create repression. The principle of ‘conservation of psychic energy’ in Jung, which I mentioned in Migglism, has particularly raised a few doubtful questions, so I thought it was worth a fuller discussion.

Psychic energy can be seen from one point of view as just physical energy in the brain. All our mental activity has to be driven by energy, in the form of glucose. When we start running out of glucose in the brain we tend to feel what psychologists call ‘ego depletion’ – it becomes harder to do anything effortful, like breaking a habit or understanding a new concept. Energy in the brain obviously comes from food processed by the body, and is part of a wider system of energy. Obviously in those wider terms, energy is not ‘conserved’ within the brain: it could be used up by the brain and turn into heat or motion which go elsewhere, without necessarily being replenished.

What Jung meant by ‘psychic energy’, however, is a particular subset of that wider physical energy. It’s the energy of our desires for particular goals, whether actual or potential. Those desires may take a conscious and immediate form where physical energy seems to be motivating us. Thus, for example, we may feel sexual desire for someone else, which motivates us towards sexual behaviour. However we can also feel that desire without acting on it, being aware that it is socially inappropriate to do so. Or we may not even be aware of the ways that such a desire is influencing us.

Such desires can gradually change their focus (for example, I might sublimate sexual desire into art). Desire, after all, is just energy, and energy can power all sorts of different processes. What we can’t do, however much we may desire it, is to instantaneously block psychic energy. If we do try to block it, it is liable to take a different form and re-emerge, just as when you try to dam the energy of a stream. It may flow somewhere else, or it may eventually flow around the blockage towards its original destination. The key thing I take from Jung’s idea of the ‘conservation of psychic energy’ is just that insight: that energy cannot be removed from the psyche at will – it has to go somewhere. It doesn’t just disappear.

The attempt to block psychic energy could take two possible forms. In repression, we really believe that we can stop the flow of energy for ever just by blocking it, and we don’t even consider the question of where that energy is going to go. In suppression, however, we recognise that the energy is there, even if we don’t want it to flow in a particular direction at the moment. Thus, if we start feeling sexual desire towards someone inappropriate, that doesn’t mean we have to try to eliminate the desire. Rather we can block it temporarily, remain aware of it, and send it somewhere else in the longer term. Absolutisation creates repression here, taking the form of a belief that we assume can simply eliminate a desire: for example, the belief that the sexual desire is just ‘wrong’. So the practice of the Middle Way involves avoiding absolutisation by trying to maintain awareness of our energies when we find it necessary to block them.

When we repress a desire, of course we do stop being aware of it for the moment. In terms of energy, we can see this in terms of a conversion from actual to potential energy. The flow of energy in your brain has already created a synaptic channel, and that channel will still be there even if nothing is flowing down it for now. That channel will be reactivated in certain conditions that bring it back into use, and in those circumstances it will be much easier for the energy to flow down the old channel than to form a new one. The ‘potential’ energy of the repressed desire thus takes the form of greater ease for the flow of future actual energy. To be released it might just need a trickle to break through the dam of repression, but because of all that potential the trickle can become a torrent much more quickly than one would otherwise expect.

But how does physical energy relate to psychic energy? Well, I don’t think they’re ultimately distinct: they’re just different ways of experiencing and labelling the same phenomena. The psychic energy in our mental system depends on the condition of our bodies, so it could hardly be independent of the physical energy system. That’s just another respect in which ‘physical’ and ‘mental’ are not ultimate or metaphysical qualities, just different contexts for experience. The total amount of energy in the psychic system can obviously change depending on the surrounding conditions, but nevertheless, much less energy may be ‘lost’ from the psychic system than we generally expect at times when we feel depleted. Instead it’s just been ‘stored’ in potential form.

So, the ‘conservation of psychic energy’ cannot be an absolute rule, nor can it even be as clear and measurable a tendency as can be documented in the case of physical energy. I don’t think the psyche can be a completely closed system within which energy is eternally conserved. Rather than ‘conservation’ of psychic energy, perhaps it would be more precise to talk about how the psychic energy system can only change incrementally rather than suddenly or absolutely. Nevertheless, we should not underestimate the ways in which energy can take unexpected potential forms in the brain, just as it can in other matter. Before the development of nuclear physics, who would have guessed that potential energy in an atom could be released by splitting it? Similarly, how can an individual guess at the unexpected energy that might be released by engaging with archetypes through love, spirituality, or art, before we experience it? We can find forms of potential energy in ourselves that we previously thought lost or impossible, and perhaps ‘potential energy’ is just a slightly less problematic term for what is often referred to as ‘the unconscious’.

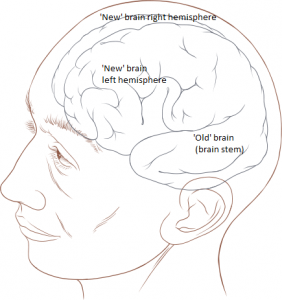

Picture: ‘Brain Power’ CCA2.0 by aboutmodafinil.com